Author: Wynter

I did not believe it at first. Twenty-five years without the chance of parole. The judge said the words in 2008, but they didn’t land. Not right away. What I remember is my wife. She cried so hard in the courtroom they had to remove her. Two of the jurors mouthed the words “I’m so sorry” to her as she looked at them in horror.

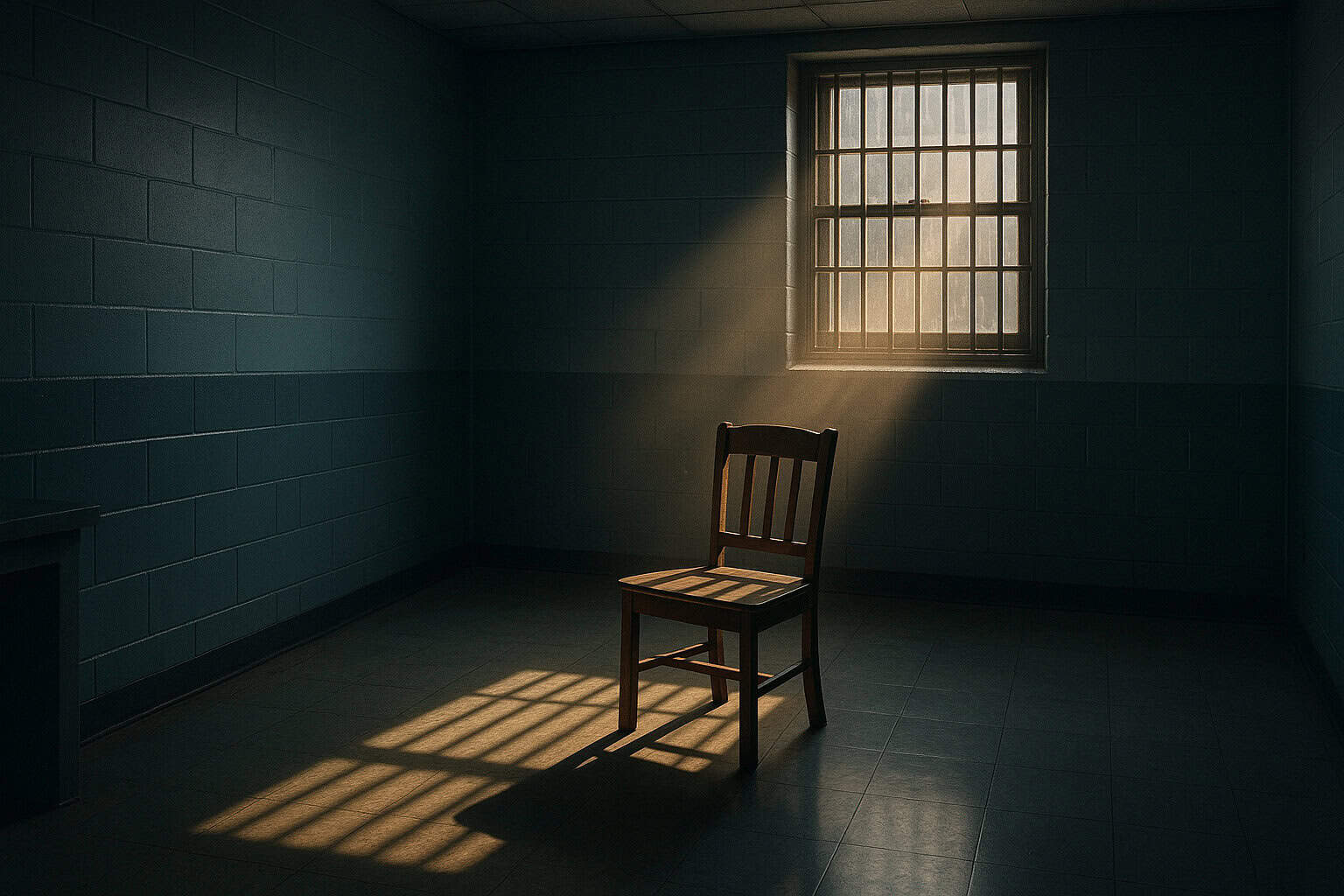

It took weeks for it to feel real. I sat alone in the county jail, waiting to go to Jackson for diagnostic processing. Just me and the weight of what was ahead.

When I got to Jackson, they stripped me naked with thirty other grown men. Humiliated us. Forced us to stand unbearably close, getting sprayed with chemicals like a dog. That’s how you enter the system — stripped down, dehumanized, treated like you weren’t even a person.

Then they sent me to the most violent dorm. I had never so much as seen the inside of a courtroom before this case. No gang affiliation. Nothing. But I was housed with only the most violent offenders.

I was robbed the second day at knifepoint for the clothes the state gave me. I had nothing. There were no officers. No one to help.

I slept a lot. Stayed to myself. Tried not to stand out. Pure survival mode.

After six weeks, they transferred me to my first camp. A level five, close-security, with only violent offenders. Not exactly the relief you might hope for. Survival mode. Day in and day out.

I finished my entire case plan within two years. I’ve worked many jobs including law library, education, vocation. I have graduated two different faith and character programs. Nothing helps to reduce my time. I’ve become a better person, but no one in the GDC cares. Instead, they want me to be the worst version of myself. The violent people are rewarded, while people like me who try to be good are punished and killed.

That’s what mandatory minimum sentencing does. It removes all hope of a person doing the right thing. No matter how good I am, no matter how much I change, it doesn’t help me to go home. I could rob, steal, and extort, it wouldn’t cause me to do any more time. I could do all the drugs I could handle without overdosing, no one would care. What’s the incentive to do the right thing?

Mandatory minimum sentencing with no possibility of parole is cruel and unusual. It takes away the one thing that might make a person want to change — hope. And without hope, the system gets exactly what it seems to want: the worst version of who we could be.