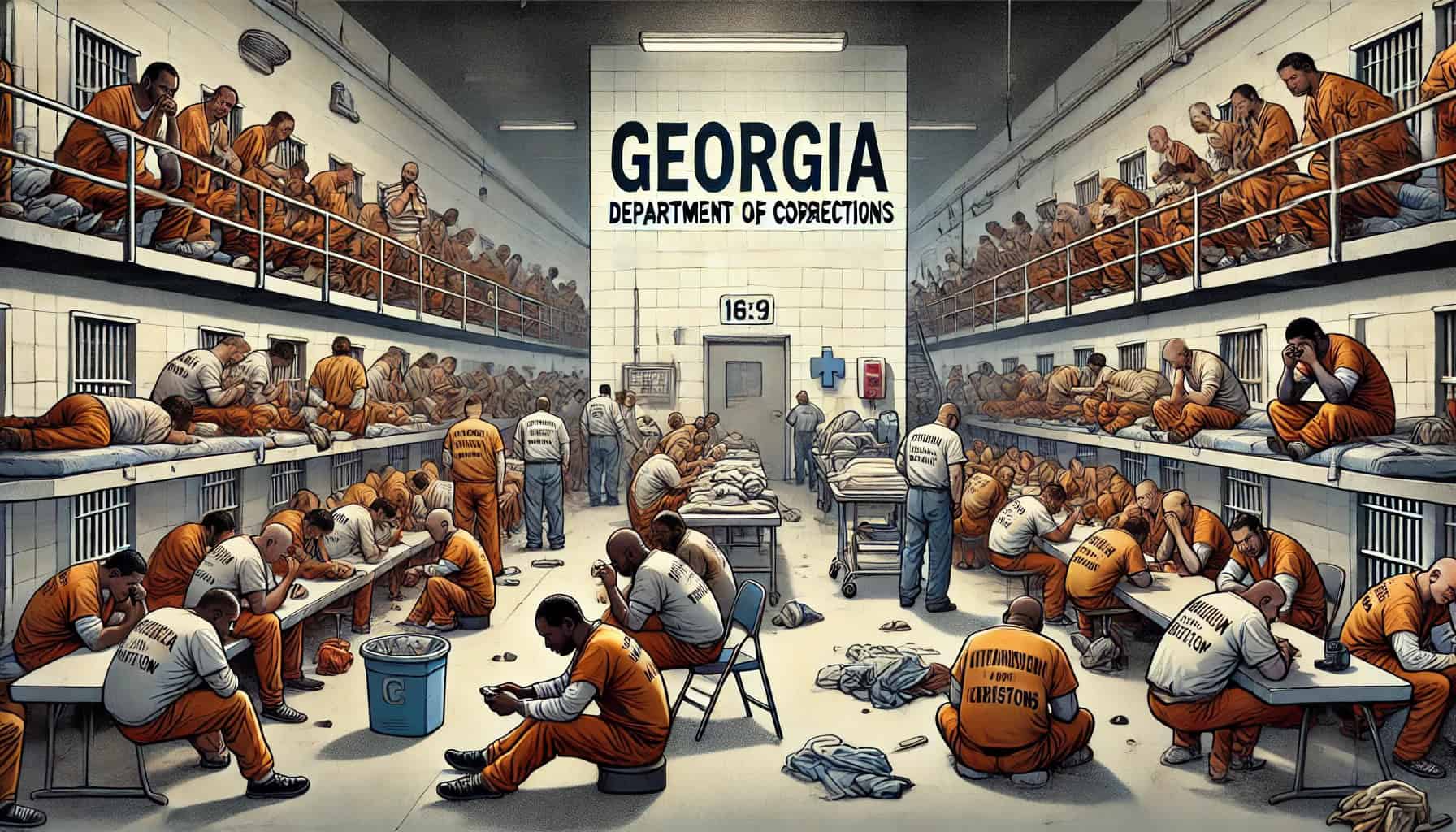

Imagine spending weeks on end confined to an area measuring just 3 feet by 4 feet—barely enough space to stand, let alone live. In Georgia’s medium-security prisons, this is the daily reality for thousands of inmates. Originally designed for single occupancy, these cramped cells now house three men each, a practice known as “triple bunking.” The consequences are severe, creating tension, unsafe conditions, and an overwhelming strain on basic services like medical care and laundry.

Inside a Triple-Bunked Cell

Cells designed for a single occupant (approximately 83 square feet) now contain triple bunk beds, a toilet and sink, three lockers, and a small desk with a single seat. After accounting for these fixtures, each inmate is left with a mere 12 square feet—an area measuring just 3 feet by 4 feet—to stand or maneuver. Beds offer only 30 inches of vertical clearance between bunks, making it impossible to sit upright comfortably. One fixed seat at the table must serve three people, forcing most to spend their time standing or lying down on their narrow beds.

Overcrowding Beyond the Cell

This overcrowding extends far beyond individual cells. Facilities constructed in the early 1990s, originally certified for 750 inmates, now regularly hold upwards of 1,700. Dormitories meant for 48 individuals currently house 120, with insufficient seating and communal space. Dining halls built to accommodate 100 inmates at a time struggle to cope with daily demands, leading to rushed meals and tension among inmates. Laundry services are overwhelmed, leaving clothes frequently unclean or damp. Mail rooms fail to process urgent legal mail promptly, medical appointments are regularly missed due to overcrowding, and counseling sessions are reduced to brief, inadequate interactions every three months.

Why Closed Security Prisons Avoid Triple Bunking

Interestingly, closed security (higher security) prisons within Georgia avoid this practice, acknowledging the fact that triple bunking increases violent incidents, mental health deterioration, and tensions among prisoners. In fact, Georgia Department of Corrections (GDC) leadership has even suggested transitioning closed security prisons toward single-occupancy cells. Yet, medium-security inmates continue to endure dangerously overcrowded conditions, highlighting a troubling inconsistency in inmate treatment.

Daily Realities of Overcrowding

- Cells designed for one or two men house three in conditions resembling confinement rather than accommodation.

- Common spaces, like recreational areas and cafeterias, cannot handle the population they currently hold.

- Essential services including medical care, laundry, and mental health counseling cannot meet the most basic needs due to overwhelming demand.

No Rehabilitation, Just Containment

With numbers vastly exceeding what facilities can safely accommodate, genuine rehabilitation programs have become impossible. Inmates are reduced to mere numbers, recognized by staff only when disciplinary problems arise. The system has shifted from rehabilitation to mere containment, a scenario that neither benefits prisoners nor promotes societal safety upon release.

Conclusion

The practice of triple bunking is not just a matter of comfort—it’s a profound humanitarian and safety crisis. It’s time Georgia acknowledges the harmful effects of these overcrowded conditions and implements humane, practical solutions, such as decarceration strategies, before tensions reach a breaking point.

Take Action: End Triple Bunking in Georgia’s Prisons

The practice of triple bunking is inhumane, unsafe, and unacceptable. Overcrowding has turned rehabilitation into a distant dream, putting prisoners and staff at constant risk. It’s time to demand better.

Your voice matters. Contact your legislators today—urge them to address prison overcrowding by ending triple bunking and implementing safe occupancy standards. Use Impact Justice AI to quickly and easily craft compelling letters, or find your legislator’s contact information here.

Together, we can push for real reform and restore dignity to Georgia’s prisons.

3 thoughts on “Triple Bunking Crisis: The Harsh Reality Inside Georgia Prisons”