Georgia faces a prison crisis marked by overcrowding, rising costs, and an aging inmate population. Decarceration – the strategic reduction of the prison population – is increasingly seen as a viable solution. This approach focuses on releasing or diverting certain categories of offenders in a way that maintains public safety. Below, we explore which inmates could be prioritized for decarceration in Georgia (particularly elderly prisoners and those with very long terms served), examine examples from other U.S. states and countries that have reduced incarceration, review crime trends following these changes, analyze the costs and benefits for taxpayers, and highlight best practices for implementing decarceration policies.

Focus on Elderly and Long-Term Inmates for Decarceration

Aging Prisoners – Low Risk, High Cost: Georgia’s prisons house a rapidly growing population of elderly inmates, presenting significant challenges both financially and ethically. As of March 2025, Georgia prisons have 12,689 inmates aged 50 or older—representing nearly 25% of the state’s total inmate population. Specifically, there are currently 7,358 inmates aged between 50–59 and another 5,331 inmates who are 60 or older. This marks a substantial increase compared to 2012, when just over 9,100 prisoners were age 50 or older.

Elderly prisoners impose considerably higher costs due to increased medical and special care needs. On average, Georgia spends about $8,500 per year on medical care for each prisoner over 65, significantly higher than the roughly $950 annually spent on younger inmates. National studies reinforce this trend, estimating that states typically spend two to three times more to incarcerate older individuals than younger inmates 1.

Despite their higher cost, older inmates pose minimal risks to public safety. Research consistently demonstrates that criminal activity sharply declines with age. Arrest rates decrease to about 2% among individuals aged 50–65, and approach nearly 0% for those over 65. Older inmates rarely reoffend upon release, as most have aged out of crime following decades of incarceration.

Considering these statistics, prioritizing geriatric release or medical parole for older and infirm inmates could significantly reduce costs without jeopardizing community safety 2. Several states have already expanded compassionate release policies targeting elderly prisoners, though Georgia’s current criteria remain restrictive. By easing these restrictions, Georgia could safely and effectively reduce its elderly inmate population, thereby addressing humanitarian concerns and alleviating financial burdens on taxpayers.

Long-Serving Inmates and Rehabilitated Offenders: Another population to consider are people who have served extremely long sentences (15–20+ years), including those convicted of violent offenses decades ago. Evidence indicates that after 15 or 20 years of incarceration, especially if the individual is by then middle-aged or older, the likelihood of reoffending is very low. In many countries, it is standard to presume release after 15–20 years, even for serious crimes, barring evidence of ongoing danger. Recidivism studies of people convicted of violent crimes and released after long terms find reoffense rates under 10%, often only 1–3%. Georgia’s current laws (such as “two-strikes” rules for certain felonies) often keep individuals incarcerated for life or decades longer than necessary. By instituting a review of cases where an inmate has already spent 15, 20, or more years in prison, the state can identify those who have been rehabilitated and no longer pose a threat. Many will have been incarcerated since youth and are now well into middle age, having long since matured. Releasing these individuals (with supervision and support as needed) not only aligns with evidence that people “age out” of crime, but it can also mitigate overcrowding.

States like California and New York have begun to reconsider extreme long-term sentences through parole reforms and “second look” laws that allow judges or parole boards to re-evaluate lengthy sentences after a set period 3. Georgia could adopt similar measures to safely decarcerate inmates who have transformed after decades behind bars.

Decarceration Success Stories in U.S. States

Several U.S. states have intentionally reduced their prison populations in recent years, offering models for Georgia. Notably, New York, New Jersey, and California each cut incarceration substantially – on the order of 20–25% – without seeing crime increases. In fact, these states outpaced national crime declines while decarcerating.

• New York and New Jersey: Between 1999 and 2012, New York and New Jersey led the nation by reducing their state prison populations by 26% each, largely through policy changes like scaling back harsh drug laws and expanding alternatives to incarceration. Over the same period, the nationwide state prison population actually grew by 10%. Importantly, crime dropped faster in these states than in the U.S. as a whole. Violent crime rates fell about 30% in New York and New Jersey during their decarceration period, compared to a 26% drop nationally. Property crime in both states also declined by roughly 30%, exceeding the national decline of 24%. These outcomes debunk the notion that more prisoners equal less crime. Both states achieved public safety improvements alongside prison population reductions. Policy analysts note that it was deliberate policy choices – sentencing reforms, parole expansions, and diversion programs – rather than underlying crime trends that drove the prison declines. In short, New York and New Jersey proved that prison populations can be cut substantially “without harming public safety.” 4

• California: California has also implemented bold decarceration measures. Facing court orders to reduce prison overcrowding in the early 2010s, California passed reforms such as Realignment (2011) – which shifted many low-level offenders from state prisons to county supervision – and Proposition 47 (2014) – which reclassified certain drug and property felonies as misdemeanors. As a result, California’s prison population fell dramatically. From 2006 to 2012 alone, the state downsized its prison population by 23%. By 2015, California had about 30,000 fewer inmates than just a few years prior, a roughly 30% drop 5. During this decarceration, California’s violent crime rate declined 21%, slightly outpacing the national violent crime drop of 19% in the same period. Property crime in California did tick down a bit less than the U.S. average (13% vs 15% nationally) , but overall crime in California remained near historic lows post-reform. Crucially, Prop 47’s changes have saved California over $800 million in incarceration costs, funds that are now reinvested in education, mental health, and drug treatment programs in communities 6. In sum, California demonstrated that rethinking sentences for low-level offenses and empowering local rehabilitation can significantly shrink a prison system. The state achieved compliance with population caps and redirected hundreds of millions of dollars to prevention – all while crime rates stayed relatively stable.

Other states have similar stories. For instance, Mississippi, South Carolina, Connecticut, Michigan, and Rhode Island each cut their prison populations by about 15–25% over roughly a decade through justice reforms 7. These states expanded parole, revised sentencing laws, and reduced re-imprisonment for technical probation violations. Notably, they saw no adverse impact on public safety; some experienced continued crime declines. Georgia can look to these examples for guidance, as they confirm that smart decarceration is compatible with improved safety and can even coincide with greater drops in crime than the national average.

International Models of Decarceration

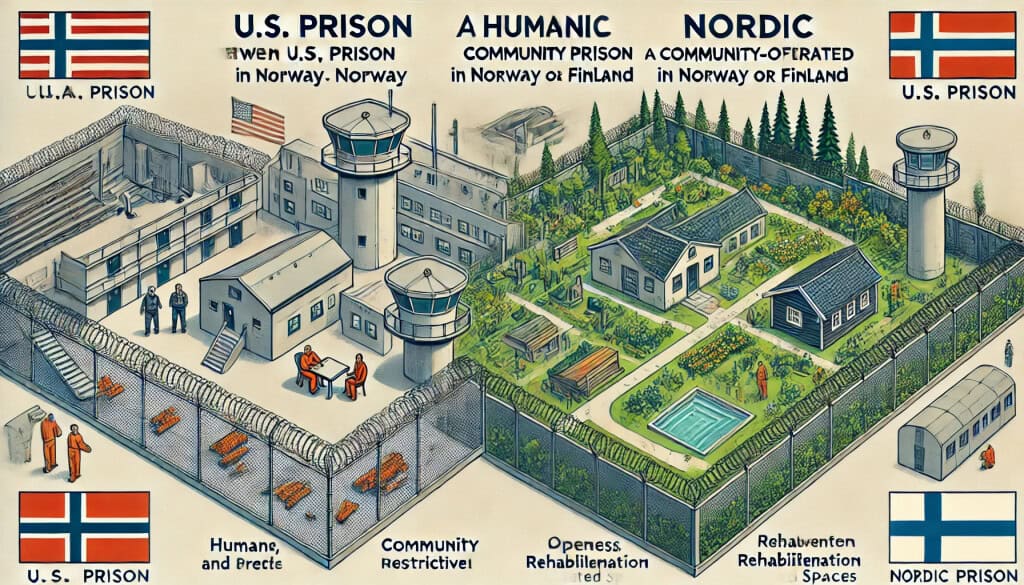

Beyond U.S. borders, many countries have embraced decarceration or have long maintained low imprisonment rates, with positive results for public safety. Finland, Germany, and Norway offer particularly instructive models.

• Finland’s Sentencing Reforms: In the 1960s and 1970s, Finland intentionally shifted away from heavy use of incarceration. At one time, Finland’s imprisonment rate was unusually high for Europe, but a liberal reform movement pushed for a more humane and proportionate justice system. Over the ensuing decades, Finland cut its incarceration rate by roughly 75% – from about 200 prisoners per 100,000 citizens in the 1950s to around 50 per 100,000 today 8. This was achieved by shortening sentence lengths (the Finns came to view long prison terms as counterproductive) and greatly expanding the use of alternatives like fines and community service. Crucially, Finnish criminologists found that crime rates operated independently of incarceration rates – in other words, reducing the use of prison did not cause crime to spike. In fact, through the 1990s as Finland’s prison population dropped to the level of its Scandinavian neighbors, the country’s crime trends were stable and closely tracked those of similar nations. Finland’s experience shows that a deliberate, policy-driven decarceration (grounded in principles of fairness and cost-benefit analysis) can succeed without endangering the public. It’s a prime example of “systematic criminal policy” resulting in fewer prisoners with no increase in crime.

• Norway and Germany – Rehabilitation Over Retribution: Countries like Norway and Germany have long kept prison sentences shorter and conditions more rehabilitative, which has translated into low recidivism and the ability to release people sooner without higher crime. In Germany, life sentences typically allow parole after 15 years, and sentences longer than 20 years are rare. Even for severe crimes, the emphasis is on eventually returning individuals to society as law-abiding citizens. Germany’s incarceration rate is about one-tenth of Georgia’s, yet Germany enjoys lower violent crime rates and a strong sense of public safety 9.

Norway is especially famous for its progressive correctional system. In the 1980s, Norway had recidivism rates as high as 70%, comparable to the U.S. today. Prisons were punitive and offered little rehabilitation, and many released individuals quickly reoffended. In the 1990s, Norway overhauled its approach, centering it on rehabilitation, normalcy, and reintegration. Prisoners in Norway gradually earn freedoms, engage in education and work, and officers build positive relationships with them. The result? Norway’s recidivism rate has plummeted to around 20% – one of the lowest in the world. Crime rates in Norway remain low, and violent incidents inside prisons are rare. Importantly, Norway proves that even people convicted of serious violent crimes can be safely released after relatively modest periods (the usual maximum sentence is 21 years) if the prison system focuses on true rehabilitation. As one Norwegian prison saying goes, “People go to court to be punished; they go to prison to become better neighbors.” This ethos, along with structured reentry programs, ensures that decarceration in Norway (through shorter sentences and high parole rates) coincides with high levels of public safety. Georgia could draw lessons from these countries: shorter maximum sentences, robust rehabilitation programs, and preparing inmates for reentry are key to safe decarceration. These international examples illustrate that incarcerating fewer people, or for shorter durations, need not compromise safety – if anything, it can improve outcomes by focusing resources on reintegration.

Public Safety Outcomes Post-Decarceration

One of the central questions in considering decarceration is its impact on crime. The evidence from both U.S. states and other countries is reassuring: crime rates generally remained stable or fell after decarceration measures were implemented. In New York, New Jersey, and California, for instance, reductions in imprisonment went hand-in-hand with historic drops in crime – violent crime declined by double digits and continued downward trends were observed. There is no indication that letting more low-risk people out of prison (or diverting them from prison in the first place) caused any increase in crime in those states. Nationwide, the period of 2008–2016 saw many states reducing incarceration modestly, and overall crime rates (especially violent crime) fell to levels not seen since the 1960s 10. Similarly, international data show no correlation between incarceration rates and crime rates – Finland’s deliberate prison population decline did not disrupt the long-term crime trend, and countries with very low incarceration (like Norway and Germany) often have low crime. In Norway’s case, recidivism was drastically cut by reforms that released people sooner, but in a supervised and supportive manner. This underscores that how people are released matters more than how many are released. In summary, research indicates that smart decarceration does not endanger public safety. In fact, by focusing on rehabilitating offenders and reserving prison for those who truly need to be there, decarceration strategies can enhance safety in the long run. Georgia can be confident that a well-designed decarceration policy – one that carefully selects candidates for release and pairs it with reentry support – is compatible with stable or even lower crime rates.

Economic Costs and Benefits of Decarceration

Reducing Georgia’s prison population could yield substantial savings for taxpayers and allow resources to be redirected to more effective public safety strategies. Here we outline key cost considerations and benefits:

• Direct Cost Savings on Prisons: Incarceration is expensive. Georgia spends roughly $21,000 per year per inmate to keep someone locked up. With about 50,000 state prisoners, that’s over $1 billion annually on prisons. These costs have ballooned over time – Georgia’s corrections budget more than doubled from $492 million in 1990 to $1.1 billion in 2010. Decarceration can significantly cut these expenses. For example, by releasing older inmates who are costly to care for, the state avoids high medical bills. One analysis in Virginia found that releasing just 62 elderly prisoners (who met criteria for geriatric parole) would save $6.6 million in a single year. To truly capture savings, decarceration must be substantial enough to close prison units or entire facilities (since many costs are fixed unless the population drops). But Georgia is at a point where even modest reductions could ease overcrowding and prevent the need to build new prisons. Those avoided capital expenditures and operating costs can save taxpayers millions.

• Reduced Strain on Healthcare and Infrastructure: An aging prison population drives up costs for hospitalization, specialized housing, and staff. Georgia’s own analysis noted that inmates 65 and over incur nearly nine times the medical cost of younger inmates. By decarcerating elderly and infirm prisoners (for whom incarceration often serves little purpose beyond warehousing), the state can alleviate the burden on prison medical services. Fewer prisoners also mean lower expenditures on food, utilities, and other day-to-day institutional needs. During the COVID-19 pandemic, it became evident that lowering prison density had public health benefits as well, reducing the spread of disease in overcrowded facilities 11. Thus, decarceration can save money on operational fronts while also improving health and safety conditions for those who remain incarcerated and staff.

• Reallocation of Resources to Prevention: Money saved from imprisoning fewer people can be reinvested in programs that improve public safety and strengthen communities. Georgia could channel funds into K-12 education, job training, mental health services, substance abuse treatment, and community policing – all areas shown to prevent crime more effectively than lengthy incarceration. California’s Proposition 47 is a prime example: the state redirected over $100 million in savings to local rehabilitation programs, mental health treatment, and trauma recovery services for crime victims 12. Such investments address root causes of crime (addiction, lack of opportunity) and reduce recidivism, creating a positive cycle. In essence, decarceration allows a shift from spending on prisons to spending on people, which can yield long-term dividends in public safety and social stability.

• Economic Contributions of Former Inmates: When individuals are released from prison and successfully reenter the workforce, they transform from state expenses into contributors to the economy. Decarceration thus expands the labor pool. Formerly incarcerated people often face barriers to employment, but with support they can find jobs and pay taxes. One study in Philadelphia found that connecting just 100 unemployed ex-offenders to jobs would generate $1.2 million in annual earnings collectively, translating to increased tax revenue and consumer spending power in the community. Over their post-release lifetimes, those 100 individuals would pay an estimated $1.9 million in additional wage taxes and $770,000 in sales taxes to the city. Scaling this up, if Georgia reduces its prison rolls by a few thousand and helps those people gain employment, the state could see tens of millions of dollars in new tax revenue over time. Moreover, families are stabilized when breadwinners come home, which can reduce reliance on social services and further boost the economy. In short, there is a significant opportunity cost to keeping potential workers locked up. Decarceration unlocks that human capital – returning people to their communities where they can work, start businesses, and otherwise contribute economically.

• Reduced Recidivism Costs: High recidivism is expensive – each cycle of arrest, prosecution, and re-incarceration drains resources. Georgia currently experiences a near 50% re-incarceration rate when including technical probation violations. By focusing on releasing those who are least likely to reoffend (such as older inmates and fully rehabilitated individuals) and providing robust reentry support, decarceration can lower recidivism. Even a modest drop in the reoffense rate yields big savings. Georgia releases about 20,000 inmates each year; if 30% (6,000 people) return to prison within 3 years, that’s a $130 million annual cost to taxpayers for those failures. Cutting the recidivism rate in half by strategic decarceration and improved reentry would free up tens of millions in avoided prison costs each year. Additionally, fewer crimes mean fewer victims and lower costs associated with law enforcement and courts. Thus, decarceration coupled with prevention efforts can pay for itself by breaking the expensive cycle of reoffending.

In sum, the cost-benefit case for decarceration is strong: Georgia can save taxpayer money on incarceration costs and reap economic benefits by having more of its residents contributing in the workforce. These savings and gains can be reallocated to more humane and effective safety measures, creating a justice system that is not only leaner but also smarter.

Best Practices for Implementing Decarceration

To ensure that decarceration is carried out safely and effectively, Georgia should follow best practices gleaned from other jurisdictions’ successes (and challenges). Key strategies include:

1. Expand Parole and Compassionate Release for Low-Risk Populations: Georgia can broaden its criteria for medical or geriatric parole to include more elderly and ill prisoners. Currently, many compassionate release policies are underutilized due to narrow eligibility and burdensome approval processes. Best practice is to make release automatic for inmates above a certain age (e.g., 60 or 65) unless there is clear evidence of danger, rather than requiring complex petitions. Parole boards should also be empowered to release people serving long sentences once they have served a substantial portion (15+ years) and are deemed rehabilitated. States like Maryland and California have started reviewing elderly lifers for release, recognizing their low recidivism risk. By implementing these measures, Georgia can safely reduce its prison population while upholding public safety and compassion.

2. Establish “Second Look” Sentencing Reviews: Introduce a mechanism to reevaluate long sentences after a set period (such as 15 years). A second look law allows judges or a review board to consider if continued incarceration is justified given an inmate’s current risk level and rehabilitation progress. The Sentencing Project recommends providing a judicial review after at most 10 years for any case. This doesn’t guarantee release but gives a chance to adjust overly punitive sentences. It acknowledges that people change over time. Washington D.C. and some states have adopted second look provisions for those who committed offenses as young people. Expanding this concept broadly can correct past excesses of the “tough on crime” era and trim prison populations by releasing people who no longer need to be confined. Georgia’s policymakers could create a review panel to systematically assess inmates who have been incarcerated for two decades or more.

3. Reform Sentencing Laws to Shorten Excessive Prison Terms: Decarceration will require front-end changes so that new admissions and sentence lengths decrease. Georgia can consider eliminating mandatory minimums for non-violent offenses and revising statutes that mandate extremely long terms. For instance, reassessing the “seven deadly sins” law (which mandates at least 10 years without parole for certain felonies) could allow more flexibility to tailor punishments. Other states have repealed “three strikes” laws or scaled back life without parole sentences. Capping the maximum sentence (say at 20 or 30 years except in extraordinary cases) is another bold reform some experts advocate, noting that sentences beyond 20 years have diminishing returns for public safety 13. By adjusting its sentencing framework, Georgia can prevent the future growth of an aging, long-term incarcerated population and make its justice system more sustainable.

4. Divert Minor Offenders and Technical Violators from Prison: A significant portion of prison admissions in many states comes not from new serious crimes, but from people revoked for probation/parole technicalities or low-level offenses. Best practices call for community-based alternatives for these categories. Georgia can expand diversion programs, such as drug courts and mental health courts, to handle offenders who would benefit more from treatment than incarceration. Additionally, limit the use of prison for technical violations of supervision (missing a meeting, failing a drug test) – instead use graduated sanctions in the community. Several states now bar re-incarceration for purely technical violations or cap the time that can be imposed (e.g., 30 days in a county jail instead of years in prison) 14. By keeping these low-risk individuals out of prison, Georgia can focus prison space on those who truly cannot be managed in the community.

5. Invest in Reentry Support to Ensure Success: Decarceration is most effective when coupled with strong reentry programs that help released individuals get back on their feet. Georgia should enhance support for housing, employment, and counseling for people coming out of prison. The first few weeks after release are high-risk for recidivism, so providing transitional services (halfway houses, job placement, mentorship) is critical. States like Michigan and Texas, which saw recidivism drops, attribute success to robust reentry initiatives 15. Georgia can partner with community organizations and invest savings from decarceration into programs that assist with substance abuse treatment, mental health care, and skills training for ex-offenders. By smoothing the transition to society, the state can further reduce reoffending – reinforcing the benefits of decarceration.

6. Engage Stakeholders and the Community: Successful decarceration requires buy-in from various stakeholders – lawmakers, law enforcement, victims’ advocates, and the public. Georgia should communicate the evidence that releasing certain populations (older inmates, those who have demonstrably reformed) is a safe and smart strategy. In states like New Jersey, bipartisan support and careful implementation plan were key to reforms that cut the prison population. Georgia might form a task force to review cases and make release recommendations, ensuring transparency and maintaining public trust. Involving community organizations in the release process (for supervision and support) can also reassure the public and aid reintegration. Ultimately, decarceration should be framed not as being “soft” on crime, but as being smart on justice – reallocating resources to strategies that work better to create a safer Georgia.

By following these best practices – from modernizing parole to bolstering reentry – Georgia can implement decarceration in a way that maximizes benefits and minimizes risks. Other states and countries have shown that a deliberate, evidence-based approach to shrinking the prison population is both feasible and effective.

Conclusion

Georgia’s prison crisis presents an opportunity to rethink the state’s approach to criminal justice. Decarceration, focused on groups like elderly and long-incarcerated individuals, is a promising solution that can relieve overcrowding and fiscal strain while upholding public safety. The experiences of places like New Jersey, California, Finland, and Norway demonstrate that fewer prisoners can mean less crime when reforms are done right. In fact, strategic decarceration can enhance public safety by freeing up resources for crime prevention and by avoiding the criminogenic effects of excessive incarceration. Georgia stands to save millions of dollars that can be reinvested in communities, all while allowing those who pose little threat to return home and contribute to society. By learning from proven models and implementing thoughtful policies, Georgia can address its prison crisis and move toward a more just, effective, and sustainable criminal justice system.

Take Action: Demand Decarceration and Reform!

Change begins when your voice is heard. Georgia’s overcrowded, inhumane prison conditions won’t improve without public pressure. We need your help to urge legislators to implement meaningful decarceration policies—especially for elderly prisoners who pose little to no risk to society.

Use Impact Justice AI to easily send powerful messages directly to your legislators and local media, advocating for sensible prison reform and immediate action on decarceration.

Additionally, you can directly contact your state representatives. To find out who represents you, including their addresses and phone numbers, visit:

Open States – Find Your Legislators

Your voice matters. Together, we can create a more humane, effective, and economically responsible justice system in Georgia.

Footnotes

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3374923/[↩]

- https://www.vera.org/publications/compassionate-release-aging-infirm-prison-populations[↩]

- https://www.sentencingproject.org/fact-sheet/second-look-laws-are-an-effective-solution-to-reconsider-extreme-sentences-amidst-failing-parole-systems/[↩]

- https://sentencingproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Fewer-Prisoners-Less-Crime-A-Tale-of-Three-States.pdf[↩]

- http://www.ppic.org/publication/crime-trends-in-california/[↩]

- https://www.cjcj.org/reports-publications/publications/proposition-47-estimating-local-savings-and-jail-population-reductions-summary[↩]

- https://www.sentencingproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Decarceration-Strategies.pdf[↩]

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/prisonindex/finland.html[↩]

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15564886.2010.485910[↩]

- https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=7046[↩]

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK566329/[↩]

- https://www.cacalls.org/prop-47/[↩]

- https://www.sentencingproject.org/reports/counting-down-paths-to-a-20-year-maximum-prison-sentence/[↩]

- https://csgjusticecenter.org/publications/confined-costly/[↩]

- https://www.urban.org/research/publication/prisoner-reentry-georgia[↩]

3 thoughts on “Decarceration as a Solution to Georgia’s Prison Crisis”