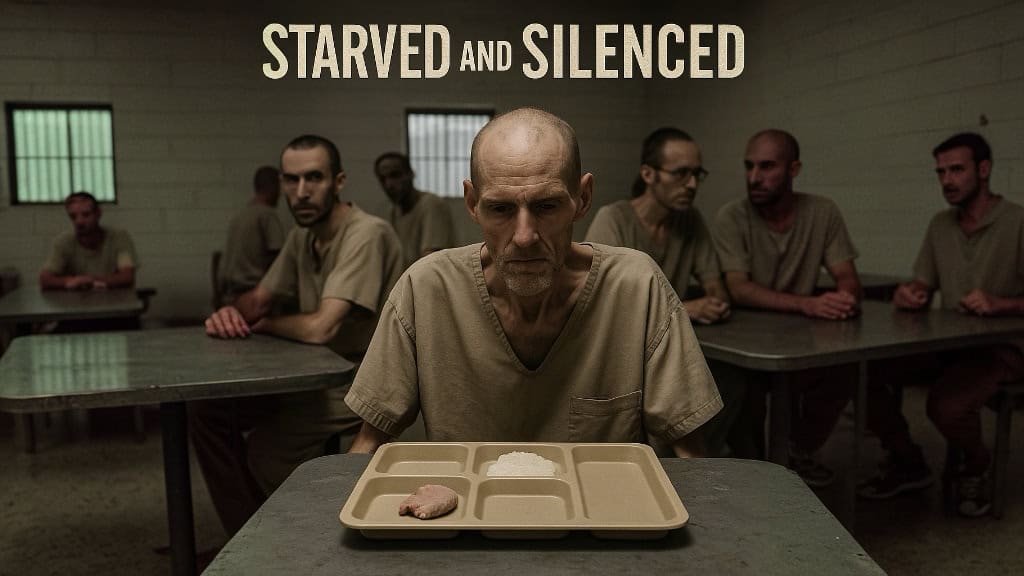

“When my son went in, he weighed about 180 pounds. Now he looks like he belongs in a concentration camp — skinny, pale, dark circles under his eyes. The Georgia DOC is wrong for how they treat people.”

Families across Georgia are sounding the alarm. From Rogers to Wheeler, Smith to Valdosta, loved ones describe men losing 30 to 50 pounds, their skin turning gray, their teeth eroding, their immune systems failing. Inmates are writing home saying they are “starving.” Some report eating toothpaste to calm hunger. Others describe black mold spreading through ceilings, water pooling in corners, and food trays that arrive cold, gritty, and nearly empty.

In the words of one mother, “They’re being slow-starved to death.”

What’s happening inside Georgia’s prisons is more than poor food — it’s systemic deprivation. Behind every tray of watered-down grits and spoiled greens lies a bureaucratic calculus that values “budget efficiency” over human life. The result is a nutritional crisis so severe that it’s fueling disease, violence, and despair across the state.

This isn’t just an oversight. It’s policy by design.

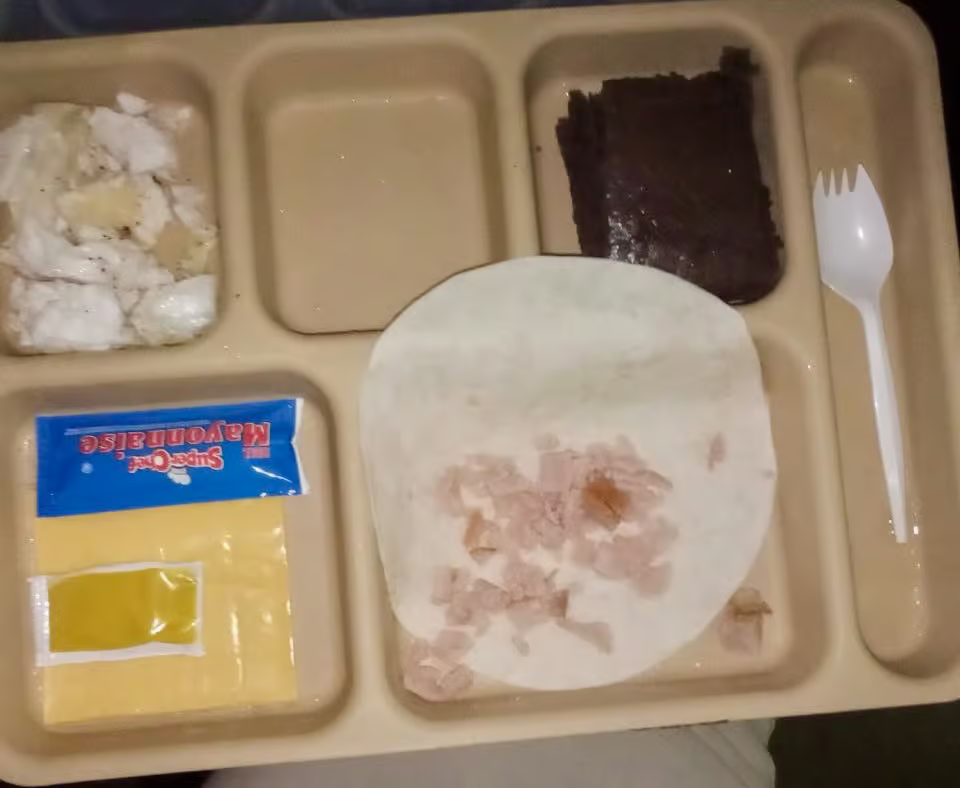

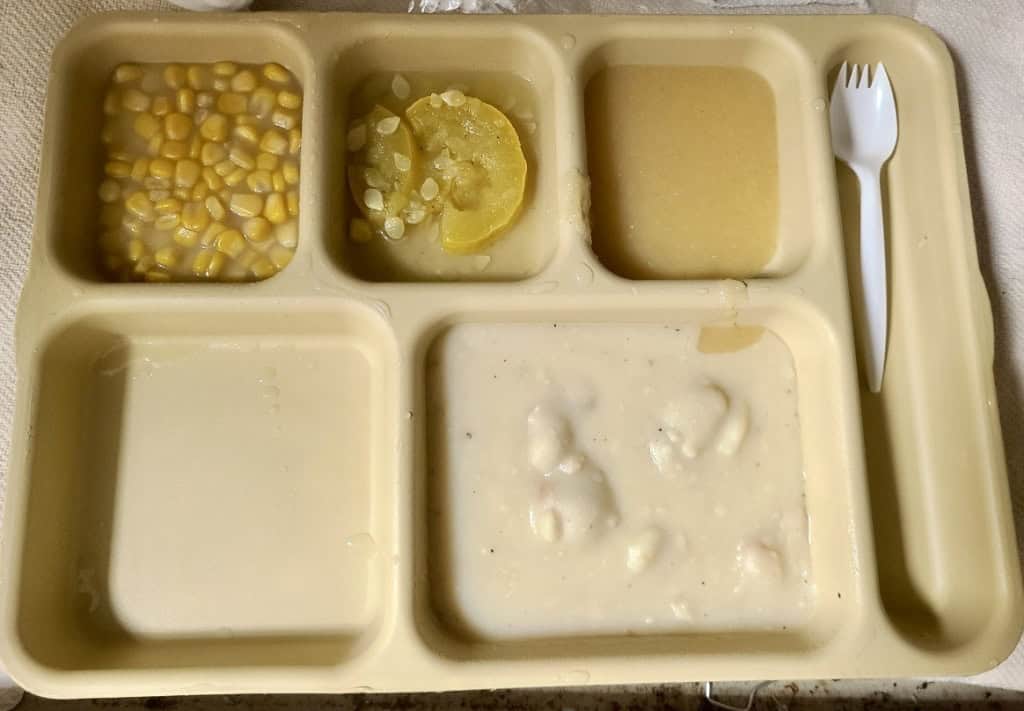

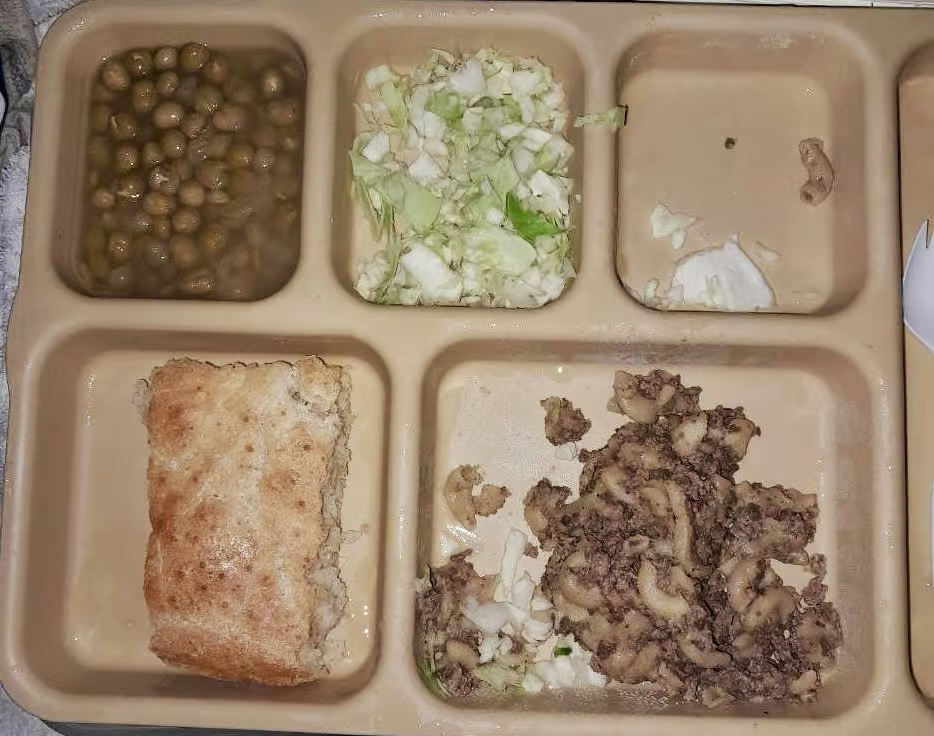

A Day on the Tray: What Georgia Prisoners Actually Eat

Breakfast

- Grits or oatmeal

- Biscuit or cake

- Two slices of bologna (occasionally replaced with two tablespoons of scrambled eggs)

- Applesauce (sometimes)

Lunch (Monday–Thursday)

- Rice mixed with frozen mixed vegetables

- One ounce of chopped chicken nuggets (occasionally served)

- One ounce of greens or a few teaspoons of corn

- Cake or bread

Lunch (Friday–Sunday)

- Single sandwich: peanut butter–corn syrup mix or a slice of bologna

Dinner

- Pasta, beans, sometimes chicken or fish

- One ounce of cubed potatoes

- Greens, or raw cabbage

- Cornbread

- Cake

According to USDA dietary guidelines, an adult male requires 2,500–2,800 calories per day, including 5–6 ounces of protein and 3–5 servings of vegetables. Georgia prisoners are lucky to receive half that. Nutritional analyses of actual prison meals have found daily calories as low as 1,200–1,400 — below the minimum for survival during prolonged confinement.

“By the time the trays get there, the grits are stuck to the pan, the milk’s clumpy, and the vegetables taste like dirt,” one former kitchen worker at Rogers said.

Shaking the Spoon: Inside Rogers State Prison

Rogers State Prison, located near Reidsville, Georgia, is where much of the state’s food for other facilities is grown and processed — yet it has become ground zero for hunger and neglect.

Former kitchen workers and current inmates describe a disturbing culture of rationing and retaliation. They say the food service superintendent, Ms. Gunner, has been running the kitchen for years with one goal: stay under budget at all costs. According to one former prisoner, known by his nickname “Hatrack,” who worked as head baker from 2022 to 2025, “She shakes the spoon — that means she doesn’t give full portions. She gets bonuses for saving money.”

“Shaking the spoon” has become prison slang for deliberately shorting food portions — a practice prisoners say is widespread across Georgia’s correctional system. Trays meant to serve 120 men are often stretched to feed 160. Portions that should weigh four ounces are served at one.

“They will starve you — I’m telling you they will starve you,” another man wrote on social media after his release.

Rogers underwent an $8.2 million kitchen renovation in 2020, reopening in August 2022 with one of the cleanest facilities in the state. But the problem was never the equipment — it’s the policy. The Department of Corrections allocates food budgets on a per-prisoner, per-day basis that often falls below $2.00. The incentive to “save” by serving less is baked into the system.

Black Mold and Rotten Air

Inmates report that mold covers ceilings and seeps into air vents above the chow hall and dorms. “They paint over the mold,” said one woman in the Facebook advocacy group. “They always get a heads-up before inspection.”

Another family member described her son’s living conditions: “He says it’s black mold everywhere. The water leaks into the ceiling and settles. He’s been sick for weeks. They won’t do anything.”

A Prison Run on Starvation

Rogers is supposed to be a food-producing hub for the entire GDC network, but workers say its kitchen operates on punishment, not purpose. Officers routinely yell at prisoners on serving lines for giving even slightly more than the measured spoonfuls.

One kitchen worker recalled: “I’d over-serve sometimes because I knew that might be the only food they’d get that day. The supervisors would cuss me out, say I was wasting state property, and kick me back to pot sink.”

The human consequences are visible. Prisoners write home about losing 20–30 pounds. They describe dizzy spells, fainting, and fights breaking out in the chow line. The DOJ’s 2024 report noted multiple deaths tied to food deprivation and dehydration across Georgia prisons — including one man found dead at Calhoun State Prison after being denied food and water for days 1.

Meanwhile, Rogers remains emblematic of how Georgia’s prison food system has turned starvation into an administrative norm.

“If everybody filed grievances against her [the food superintendent], it might stop,” said one former inmate. “But people are scared. You speak up, you get written up or transferred.”

Part 2 – The Statewide Crisis: Starving for Control

What’s happening at Rogers is not an exception — it’s the template.

Across Georgia’s 34 state prisons, food deprivation has become a management strategy, not a malfunction. When a system runs with half its staff gone, crumbling facilities, and gang networks in control, food becomes the easiest tool to control behavior, cut costs, and mask neglect.

Starvation by Policy

The U.S. Department of Justice’s 2024 findings report on Georgia prisons confirmed what families have said for years: the state’s prison system is operating below constitutional minimums. Staffing vacancies exceed 50% statewide, with some prisons running night shifts with only one or two officers overseeing 1,700 men 1.

Under these conditions, oversight of food service is almost nonexistent. The DOJ documented that at many facilities, no officer enters segregation units for days, meaning meals can go undelivered without detection. At Calhoun State Prison, one man was found dead and decomposing in his cell after missing meals and water for two days; cause of death: dehydration and renal failure.

At Ware State Prison, the neglect turned explosive. In August 2020, prisoners staged a riot after days without proper food and medical care, setting fires and seizing keys when staff failed to respond. Similar uprisings have flared at Smith, Wheeler, and Baldwin.

But for every riot that makes the news, hundreds of silent deaths go unreported. Families get brief phone calls, no details, and autopsy results months later. The GDC stopped including cause of death in monthly mortality reports in 2024 — an intentional blackout that hides starvation, dehydration, and neglect behind bureaucratic language like “undetermined” or “natural causes” 2.

Empty Calories, Empty Promises

The Georgia Department of Corrections claims its menus meet all nutritional standards. In practice, those menus are fiction. Former prisoners across the state report the same pattern: tiny portions, missing items, cold food, spoiled milk, and “meat” unfit for consumption.

A 2023 nutrition analysis of actual meals from multiple Georgia prisons found that inmates received less than 1 serving of vegetables per day, 40% of required protein, and 35% of necessary dairy. The menus lacked vitamins A, D, and E entirely, while delivering 300% of recommended sodium levels — a diet that creates hypertension, diabetes, and kidney disease in a population already at risk.

The GDC spends between $1.77 and $2.20 per prisoner per day on food, far below the USDA’s $10 minimum for an adult male diet. That number drops even lower when contractors like Trinity Services Group take their cut. The result is not just hunger — it’s structural malnutrition.

The Economics of Starvation

Georgia’s prison food policy looks thrifty on paper. But every dollar “saved” on food triggers $6 to $10 in healthcare, security, and long-term societal costs.

Research by Impact Justice and The Marshall Project shows that states spend an average of $33,000 annually per prisoner, with healthcare consuming 19% of costs while food represents just 4%34. When nutrition drops below basic survival levels, chronic illness skyrockets. Diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease — all linked to sodium-heavy, nutrient-poor diets — drive up medical costs exponentially.

Inmates with diabetes cost 2.3 times more to treat than those without. Yet Georgia’s prison meals routinely contain triple the recommended sodium and one and a half times the cholesterol. Each untreated case of diabetes or hypertension means recurring hospitalizations, dialysis, and medication — all billed to the taxpayer.

Violence: The Hidden Price Tag

Hunger breeds desperation, and desperation breeds violence.

The DOJ’s investigation documented over 1,400 violent incidents across Georgia prisons in just 16 months — fights, stabbings, assaults, and homicides. The link between malnutrition and aggression is scientifically proven: nutritional deficiencies, especially in omega-3 fatty acids, B-vitamins, and magnesium, directly impair brain chemistry that regulates mood and impulse control.

In the landmark Oxford University study by Dr. Bernard Gesch, prisoners receiving basic vitamin and mineral supplements committed 37% fewer violent offenses than those given placebos56.

Subsequent studies in the Netherlands and California replicated results with reductions as high as 47–61%. The cost: about $50 per inmate per year — less than a week’s worth of Georgia’s food budget.

Georgia, however, has chosen the opposite approach: cut calories, strip nutrients, and spend millions managing the chaos that follows.

The False Economy

The math is brutal.

Prison administrators claim to save pennies on food while spending dollars cleaning up the fallout. Adequate nutrition — even a modest increase of $1,000 per prisoner annually — would save $1,100 in security costs and $700–$1,000 in healthcare costs, creating net savings of $200–$1,200 per prisoner per year. Multiplied across Georgia’s 47,000 inmates, the state could save $56 million annually by feeding prisoners properly instead of starving them.

And that’s not including the human cost. As one mother put it, “They spend more on pepper spray than they do on food.”

Part 3 — The Physiological and Psychological Toll

Inside Georgia’s prisons, the human body becomes both the battlefield and the evidence of neglect.

Inmates’ faces hollow out, muscles waste, and immune systems collapse under the combined pressure of malnutrition, stress, and confinement. Hunger isn’t a side effect — it’s the mechanism of control.

Starving the Body

Doctors call it protein-energy malnutrition, a condition more commonly associated with war zones and famine-struck nations. In prison, it manifests as weight loss, dizziness, brittle nails, swollen gums, chronic fatigue, and fainting. Over time, the body begins consuming itself — first fat stores, then muscle, including the heart.

In cases documented by advocates, Georgia prisoners have lost as much as 50 pounds in six months, while others described waking up trembling from hunger. Medical neglect compounds the crisis: most facilities have no full-time physicians, and sick call requests often take weeks.

A former Rogers inmate wrote: “You can’t think straight when you’re hungry all the time. You get mean. Everything starts to feel like survival.”

The DOJ’s findings confirm the lethal synergy between starvation and neglect. At Calhoun, Ware, and Smith State Prisons, prisoners died of dehydration, untreated diabetes, and kidney failure after prolonged food and water deprivation 1.

Immune System Collapse

The CDC reports that incarcerated people are six times more likely to contract foodborne illness than the general public. That risk spikes in prisons serving spoiled or unwashed vegetables and clumpy milk, as prisoners at Rogers have described. Inmates exposed to black mold and filthy kitchens are constantly sick with respiratory infections that never resolve.

Low protein and vitamin deficiencies reduce antibody production and weaken T-cell function. In Ethiopia’s Hawassa Central Prison, an outbreak of scurvy (vitamin C deficiency) killed multiple prisoners after five months without fruit or vegetables. Similar deficiencies are quietly appearing in Georgia — not through famine, but through policy.

The Mental Health Connection

Hunger also dismantles the mind.

Scientific research spanning four decades has found that nutrient deficiencies directly affect neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine, altering mood, judgment, and impulse control.

Low B12 and folate levels cause anxiety, paranoia, and even psychosis. Vitamin D deficiency, common among prisoners deprived of sunlight and fresh food, is linked to major depression. Magnesium deficiency increases aggression and restlessness.

Studies of confined populations show that malnutrition leads to elevated stress hormones (cortisol) and changes to the HPA axis, the brain’s stress-response system. Combined with constant noise, isolation, and fear, this creates a neurochemical environment of permanent fight-or-flight — a recipe for chaos.

“It’s not just hunger,” said one former prisoner. “It’s the feeling that nobody cares if you live or die.”

The Privatization Disaster: Starving for Profit

Behind the shortages and spoiled food lies a multibillion-dollar industry.

Feeding the incarcerated has become a lucrative business controlled by a handful of private corporations — notably Aramark, Trinity Services Group, and Summit Correctional Services.

Together, they control the majority of prison food service contracts nationwide, earning billions annually while slashing costs at the expense of those behind bars3.

A Profitable Hunger

Each company operates under the same business model: promise savings, then quietly cut corners.

Meals shrink. Meat becomes “soy-based blend.” Food marked “Not for human consumption” appears on invoices. When prisoners complain, they are punished or ignored.

Mississippi ended its Aramark contract in 2021 after a lawsuit revealed spoiled food contaminated with rat and insect feces. Michigan terminated its contract in 2015 after maggots were found in multiple prison kitchens. In Georgia, Aramark and Trinity continue operating under similar terms — even after repeated allegations of unsafe food and missing portions.

The profit incentives are perverse. The same companies that underfeed prisoners also own commissary suppliers. Aramark owns Union Supply Group; Trinity shares ownership with Keefe Commissary Network. In other words, the worse the food in the chow hall, the more money they make from commissary sales.

As attorney Marcy Croft, who sued Mississippi’s Department of Corrections, put it:

“Crappy food is being paid for twice. And then the state is paying for the medical care on top of that.”3

The Georgia Connection

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution’s ongoing investigation found that Georgia’s Department of Corrections has repeatedly falsified or withheld information about deaths, food quality, and facility conditions 7.

Federal Judge Marc Treadwell, in his 2024 contempt order, stated bluntly:

“The Court has long passed the point where it can assume that even sworn statements from the defendants are truthful.”

The GDC’s deception extends to its food service. Official menus show balanced meals with chicken, vegetables, and fruit — but inside, prisoners receive single sandwiches, a scoop of starch, and water with floating debris.

At Rogers, former workers say the kitchen “serves less than the menu calls for on purpose,” pocketing bonuses for staying under budget. The DOJ confirmed that such practices meet the legal threshold for “deliberate indifference” — a constitutional violation under the Eighth Amendment.

“This is not just neglect,” said one former officer. “It’s cruelty wrapped in policy.”

A Broken Feedback Loop

Because inspections are scheduled in advance, facilities have days to “stage” compliance. Prisoners report manic cleaning sprees and sudden bursts of good food right before visits, followed by immediate return to the usual starvation rations. Even when violations are found, inspectors rarely shut kitchens down — because that would mean closing the prison’s only food source.

As one advocacy leader put it:

“If a restaurant served food like this, it would be condemned. In Georgia’s prisons, it’s just another day.”

Part 4 — What Works: Feeding People, Saving Lives

The tragedy unfolding in Georgia’s prisons isn’t inevitable — it’s engineered. But the solutions are already known, proven, and achievable. Other states have shown that when prisons feed people adequately, violence drops, health improves, and costs decline. The only thing missing in Georgia is the will to change.

Models That Work

Maine: The Garden Model

At the Mountain View Correctional Facility, prisoners help operate a 2.5-acre garden and 7-acre apple orchard. The produce — over 150,000 pounds of fruits and vegetables annually — supplies the prison kitchen and local food banks. This program saves roughly $100,000 a year while providing incarcerated people with education and transferable skills through the University of Maine’s Master Gardener program. Meals cost $4.05 per day, still below the national USDA guideline but dramatically higher in quality.

Washington: Sustainability in Prisons

Washington’s Sustainability in Prisons Project, a partnership between Evergreen State College and the Department of Corrections, turns food service into education and rehabilitation. In 2018 alone, participants harvested 246,700 pounds of fresh produce distributed across 11 prisons and local food banks. Beekeeping, composting, and aquaponics programs have reduced waste while improving morale and food quality.

Both programs prove that self-sufficiency and nutrition are not luxuries — they are necessities. They also demonstrate that rehabilitative food systems can reduce recidivism by equipping prisoners with tangible, life-building skills.

The Nutrition Intervention Breakthrough

Multiple international studies confirm that small nutritional interventions can have massive behavioral payoffs. Oxford’s landmark research found that basic vitamin and mineral supplementation reduced violent incidents by 37% 8. Similar programs in the Netherlands and California achieved 30–47% reductions in aggression — often within weeks.

For Georgia, these findings represent a missed opportunity. The supplements cost less than $50 per prisoner per year — a rounding error in a system that spends billions annually yet cannot meet basic human needs.

A Blueprint for Georgia

Georgia’s crisis isn’t rooted in ignorance — it’s rooted in indifference. Every piece of evidence points to the same conclusion: feeding people properly saves money, reduces violence, and upholds human dignity. The solutions are simple, scalable, and overdue.

Immediate Actions Georgia Can Take

1. Double the Food Budget.

Increase per-prisoner food spending from $2.00 to $4.00 per day — still below USDA minimums but enough to meet basic nutritional needs. Even this modest investment could reduce violence and healthcare costs by tens of millions annually.

2. Implement Nutrient Supplementation Programs.

Provide multivitamins, essential fatty acids, and mineral supplements costing less than $50 annually per person. Studies prove this reduces aggression, anxiety, and suicidality more effectively than any psychological program.

3. End the Food-For-Profit Model.

Terminate or strictly regulate contracts with private food providers like Aramark and Trinity Services Group. Prevent contractors from also operating commissary companies — a clear conflict of interest that incentivizes starvation.

4. Return to In-House Food Service.

States like Michigan and Mississippi saved money and improved conditions by ending privatized food contracts. Rehiring union kitchen staff improves accountability and oversight.

5. Build Prison Gardens and Local Food Partnerships.

Repurpose prison land for gardens, orchards, and greenhouses. Partner with Georgia’s agriculture programs and local universities for training and oversight.

6. Conduct Surprise Kitchen Inspections.

Eliminate the advance-notice inspections that allow manic cleanup sprees. Empower independent monitors to photograph actual meals and publish findings publicly.

7. Transparency and Accountability.

Reinstate cause-of-death reporting in GDC mortality logs. Require public access to meal budgets, vendor contracts, and nutritional audits.

A Moral and Economic Imperative

The United States spends more incarcerating a person than educating one. Georgia spends millions each year managing violence and disease — both preventable with adequate nutrition.

It is a false economy to starve people to save money. The result is death, disorder, and lifelong health burdens that follow prisoners home when they are released.

“You can’t rehabilitate someone you’re starving,” said one former inmate. “They talk about correction, but all they do is break you.”

Every year, 95% of Georgia’s prisoners return to their communities. Their health — and the diseases born behind bars — become public health problems. When a man leaves prison diabetic, hypertensive, or mentally ill because the state refused to feed him properly, taxpayers pay again.

Nutrition is not charity. It’s strategy — one that protects staff, saves money, and affirms that human life has value.

Call to Action: What You Can Do Right Now

Prisoners’ lives depend on what we do next. Georgia’s families and citizens have the power to demand transparency, accountability, and reform.

1. Use ImpactJustice.AI

Go to ImpactJustice.AI — a free tool created by the GDC Accountability Project and Georgia Prisoners’ Speak.

There, you can automatically generate and send personalized letters to:

- Georgia state legislators

- The Georgia Department of Corrections

- Local media outlets

- The U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division

These letters demand full investigations into prison food conditions and urge the state to end privatized food contracts.

2. Contact Your Legislators Directly

Find your Georgia representatives using openstates.org/find_your_legislator or the Georgia General Assembly’s website.

Ask them to:

- Demand independent nutritional audits of all GDC facilities

- Support funding for food reform and mental health programs

- Enact oversight of private food service vendors

3. File Formal Complaints

- U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division (CRIPA):

https://civilrights.justice.gov/report

- Georgia Department of Public Health (Environmental Health):

Report unsafe food, water, or mold conditions in prisons.

- State Inspector General:

Request investigations into GDC misuse of funds and false reporting.

Document everything — names, dates, photos, and descriptions of meals or health symptoms. Each record helps build the case for federal intervention.

4. Share and Speak Out

Share this article on social media. Talk about it at church, at work, in schools, and with local journalists. The public’s silence is the GDC’s shield — breaking that silence is the first step toward justice.

Tag posts with #GeorgiaPrisons #StarvedAndSilenced #PrisonReformNow

5. Support Families

Write, call, and send funds safely through approved channels. Families are the last line of defense for those inside — and the first voices the state tries to silence.

Final Word

The hunger inside Georgia’s prisons is not accidental — it’s systemic. It’s the predictable outcome of a state that sees prisoners as costs to be reduced instead of lives to be rehabilitated.

Until Georgians demand change, people will keep dying unseen, their bodies wasting away in silence while officials falsify reports and corporations count profits.

As the DOJ concluded, “People are assaulted, stabbed, raped, and killed or left to languish inside facilities that are woefully understaffed.” 1

That languishing begins with hunger.

Every meal withheld is a violation. Every empty tray is a death sentence delivered slowly.

Georgia can choose to end it — but only if we refuse to look away.

“This is what ‘rehabilitation’ looks like in Georgia.”

Further Reading & Related Reports

To explore more about Georgia’s prison food crisis, systemic neglect, and the nationwide impact of mass incarceration policies, these investigations and reports provide deeper context.

From Georgia Prisoners’ Speak

Examines how inadequate meals and chronic hunger are directly driving violence, despair, and unrest inside Georgia’s prisons.

A firsthand look at what prisoners are actually served — the meager portions, the cold food, and the silence that follows.

Exposes how “accreditation” standards hide the grim truth of Georgia’s prison conditions from the public and policymakers.

Breaks down how the state allocates food funding — revealing that prisoners are fed on less than $2 a day.

Explores the link between nutrition, brain chemistry, and aggression, showing how food policy directly impacts safety.

Summarizes the most frequent food-related complaints reported by Georgia prisoners and their families.

Investigates how state control and lack of oversight allow corruption, deprivation, and cover-ups to flourish within the GDC.

Independent Journalism & Government Reports

The DOJ’s official report exposing widespread violence, neglect, and human rights violations across Georgia’s correctional facilities.

A multi-part series detailing rampant corruption, falsified data, and record-breaking levels of violence inside Georgia’s prisons.

Reveals how the GDC misled federal investigators and lawmakers about deaths, falsified reports, and ongoing systemic failures.

Documents the state-commissioned report confirming emergency-level staffing shortages, gang control, and failing infrastructure.

A national overview of how industrialized, low-quality prison meals fuel violence, poor health, and mass incarceration.

Investigates how private food service companies profit from starvation and commissary markups in prisons across the U.S.

Advocacy & Action Tools

Generate and send advocacy letters to Georgia legislators, media outlets, and the DOJ demanding prison reform and accountability.

File an official complaint about unsafe, inhumane, or unconstitutional prison conditions under the Civil Rights of Institutionalized Persons Act.

Report issues related to mold, unsafe drinking water, or unsanitary food preparation within Georgia correctional facilities.

The following is the list of sources for this article:

Prison Policy Initiative

Impact Justice

Department of Justice

The Marshall Project

- https://www.themarshallproject.org/2015/07/07/what-s-in-a-prison-meal

- https://www.themarshallproject.org/2025/03/08/food-business-michigan-prison-mississippi

Atlanta Journal-Constitution

- https://www.ajc.com/news/public-affairs/jail-food-complaints-highlight-debate-over-outsourcing-public-services/PpVFFB46kOLExOmv6UX7SJ/

- https://www.ajc.com/news/investigations/georgia-prison-officials-have-repeatedly-presented-false-or-misleading-information-to-federal-investigators-state-lawmakers-and-a-federal-judge/H76M74I6L5F5DKXEYSSZEQSLGY/

- https://www.ajc.com/news/gordon-county-inmates-underfed-human-rights-group-alleges/csgdakqQ5BP2fmDMEKEmsI/

Other Georgia Sources

- https://filtermag.org/georgia-prison-budget-commissary/

- https://gps.press/mealtime/ (Georgia Prisoners’ Speak)

- https://gps.press/feeding-injustice-the-inhumane-quality-and-quantity-of-prison-meals-in-georgia/

Healthcare Cost Studies

- https://www.vera.org/publications/price-of-prisons-2015-state-spending-trends/price-of-prisons-2015-state-spending-trends/price-of-prisons-2015-state-spending-trends-prison-spending

- https://www.pew.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2017/10/prison-health-care-costs-and-quality

- https://www.pew.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2017/12/15/prison-health-care-spending-varies-dramatically-by-state

- https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-17-379

Academic/Medical Sources

- https://publichealthpost.org/health-equity/prison-nutrition-cooking-up-options-for-those-serving-time/

- https://sites.brown.edu/publichealthjournal/2023/05/02/beyond-the-food-how-prison-nutrition-policy-contributes-to-lasting-chronic-disease/

- https://www.cspi.org/blog/public-health-implications-prison-and-jail-food

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35916664/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20014286/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17392137/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24500658/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24422845/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35337631/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16332379/

PMC (PubMed Central) Articles

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11420884/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9757498/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10780435/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10729832/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC81630/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12130097/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5641835/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11509786/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10255717/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4693953/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4175558/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7077099/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8858590/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4235202/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9312494/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3984258/

Violence and Nutrition Studies

- https://www.sciencefocus.com/the-human-body/prison-food-nutrition-violence-mental-health

- https://sanquentinnews.com/growing-research-shows-impact-of-poor-nutrition-on-prison-violence/

- https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/evolutionary-psychiatry/201105/diet-and-violence

- https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/pn.37.19.0026

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/26836145_The_Theory_Diet_Causes_Violence_The_Lab_Prison

- https://library.fabresearch.org/viewItem.php?id=7275

- https://wellbeingjournal.com/crime-and-food/

Privatization/Contractor Issues

- https://investigate.afsc.org/company/aramark

- https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/prison-strike-protest-aramark

- https://www.prisonlegalnews.org/news/2024/may/1/aramark-prison-food-thought/

- https://www.prisonlegalnews.org/news/2016/oct/14/hungry-prisoners-dread-privatized-food-services/

- https://www.prisonlegalnews.org/news/2021/jan/1/georgia-prisoners-lacked-food-water-leading-melee/

- https://www.cbsnews.com/detroit/news/states-ends-prison-food-contract-with-aramark-but-is-new-contractor-riddled-with-hunger-issues/

- https://www.governing.com/archive/gov-private-food-service-prisons-aramark-trinity-ohio-michigan.html

- https://civileats.com/2018/08/20/michigans-failed-effort-to-privatize-prison-kitchens-and-the-future-of-institutional-food/

- https://thinkprogress.org/snyder-prison-food-reverse-f8559aa3360b/

- https://federalcriminaldefenseattorney.com/aramarks-correctional-food-services-meals-maggots-and-misconduct/

- https://www.vice.com/en/article/why-1200-michigan-inmates-are-protesting-their-prisons-food/

- https://www.corrections1.com/investigations/federal-judge-imposes-fines-monitor-on-ga-prison

- https://prisonjournalismproject.org/2023/09/10/getting-rich-providing-awful-prison-food/

- https://oklahomavoice.com/2025/02/08/oklahoma-looks-to-privatize-prison-food-service/

Legal/Historical Sources

- https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/429/97/

- https://dash.harvard.edu/bitstream/handle/1/8848245/Naim05.html?sequence=2

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prison_food

- https://theconversation.com/what-we-can-learn-from-the-often-gruesome-history-of-food-in-hospitals-and-prisons-76659

- https://jn.nutrition.org/article/S0022-3166(22)07500-9/fulltext

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vitamin_B12_deficiency

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal_axis

Other Health/Nutrition Sources

- https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/evidence-based-research-role-zinc-and-magnesium-deficiencies-depression

- https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychiatry/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.933704/full

- https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/aging-neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnagi.2015.00052/full

- https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/aging-neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnagi.2013.00033/full

- https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/endocrinology/articles/10.3389/fendo.2014.00073/full

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S241464472030004X

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S266645932500040X

- https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/02/150225094109.htm

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK201966/

- https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2607/10/8/1486

- https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/17/9/1551

- https://www.mdpi.com/2218-1989/14/10/549

- https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/22987-malnutrition

- https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal-hpa-axis

- https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/nutritional-disorders/undernutrition/protein-energy-undernutrition-peu

- https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/50622

- https://www.humintell.com/2025/08/junk-food-fuels-violence-the-science-of-diet-aggression/

- https://research.monash.edu/en/publications/omega-3-fatty-acids-and-the-brain-review-of-studies-in-depression

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-020-19861-z

- https://www.inrae.fr/en/news/links-between-nutrition-and-brain-how-maternal-omega-3-deficiency-can-influence-behavioural-development-offspring-animals

- https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0028451

- https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/can-not-enough-nutrients-cause-brain-fog

- https://connect.extension.org/blog/nutrient-deficiencies-and-the-mind-the-mental-health-consequences-of-malnutrition?nc=1

- https://lonestarneurology.net/others/the-importance-of-omega-3-fatty-acids-for-brain-health/

- https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/metals-and-mental-health/

- https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13668-025-00668-7

- https://aquila.usm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1713&context=masters_theses

- https://economicthinking.org/unhealthy-and-high-carb-prison-food-obese-diabetic/

- https://www.vera.org/news/cheap-jail-and-prison-food-is-making-people-sick-it-doesnt-have-to

- DOJ Findings Report: https://www.justice.gov/d9/2024-09/findings_report_-_investigation_of_georgia_prisons.pdf[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- AJC investigation: https://www.ajc.com/news/investigations/georgia-prisons-the-ajcs-investigation-into-corruption-dysfunction-and-violence/P3GTS77W4RGHLN5GLJSS6WCV2Y/[↩]

- The Big Business of Bad Prison Food — The Marshall Project: https://www.themarshallproject.org/2025/03/08/food-business-michigan-prison-mississippi[↩][↩][↩]

- The Marshall Project, What’s in a Prison Meal: https://www.themarshallproject.org/2015/07/07/what-s-in-a-prison-meal[↩]

- Influence of supplementary vitamins, minerals and essential fatty acids on the antisocial behaviour of young adult prisoners. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181:22–28: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12091259/[↩]

- Journal page (British Journal of Psychiatry, DOI 10.1192/bjp.181.1.22):

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/the-british-journal-of-psychiatry/article/influence-of-supplementary-vitamins-minerals-and-essential-fatty-acids-on-the-antisocial-behaviour-of-young-adult-prisoners/04CAABE56D2DE74F69460D035764A498[↩] - AJC Investigation: https://www.ajc.com/news/investigations/georgia-prison-officials-have-repeatedly-presented-false-or-misleading-information-to-federal-investigators-state-lawmakers-and-a-federal-judge/H76M74I6L5F5DKXEYSSZEQSLGY/[↩]

- Oxford Study on Nutrition and Violence: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12091259/[↩]

It’s all true. It’s true and all of the staff is aware and doing nothing to correct it. From the top GDC official to the lowest level officers they are aware. They’re aware that the gangs run the prisons and the drugs and phones are brought in by staff. Yet they do nothing.