When the public thinks of corruption, they often picture backroom deals or political favors. But in Georgia, corruption is not confined to shadows—it lives in plain sight, inside prison walls, behind court filings, and within the very institutions tasked with upholding the law.

For years, Georgia’s Department of Corrections (GDC) has been plagued by scandal: prison staff caught smuggling contraband, gang-run dorms, unreported inmate deaths, and conditions so dangerous they violate the Constitution. But the deeper betrayal lies not just in the violence or the neglect—it lies in the cover-up.

This story goes beyond the GDC. It reveals how the Georgia Attorney General’s Office has shielded those responsible, obstructed investigations, and withheld evidence in court. Together, these institutions have built a system that punishes those who speak out and protects those who abuse power.

What happens when the state’s top law enforcement agencies commit more crimes than the people they incarcerate? This investigation seeks to answer that question.

Corruption and Crime Within Georgia’s Prison System

Georgia’s Department of Corrections (GDC) has been rocked by a wave of internal corruption over the past decade. An investigative series by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution (AJC) found more than 425 cases of GDC employees arrested since 2018 for on-the-job crimes. The vast majority – at least 360 – involved contraband smuggling schemes, with prison guards, nurses, cooks, and even high-ranking officers caught bringing in cell phones, drugs, and other illegal items for inmates. These “dirty” staff members often received hefty payoffs (sometimes thousands of dollars) and enabled and even encouraged inmates to run elaborate drug-trafficking, cyberfraud, extortion, and even murder plots from behind bars.

“I’m in prison, but I’m not a crook,” says one inmate that we have chosen to keep anonymous for his protection. “I was approached by a staff member who told me that she was told I was a player. She kept on me for weeks about selling some items that she was bringing in. I told her I wasn’t interested, but she didn’t believe me. After that she gave me odd glances whenever I came across her. I was becoming afraid she would try to make something up to get me in trouble. Fortunately she went to work at another prison. I understand that she followed her boyfriend to that prison.”

The corruption has fueled violence inside prisons and facilitated stunning crimes victimizing people on the outside, as prisoners could coordinate offenses using smuggled phones and networks of accomplices. One Georgia prosecutor described it as a “chronic, persistent issue,” likening the fight to “a cycle of ‘whack-a-mole’ – as soon as one corrupt officer is arrested, another springs up to take their place.”

Recent cases underscore how deep the misconduct runs. Even a prison warden was implicated: in February 2023, GDC Warden Brian Adams of Smith State Prison was fired and arrested on charges including conspiracy to violate Georgia’s RICO Act, bribery, making false statements, and violating his oath of office. A Georgia Bureau of Investigation (GBI) probe (requested by the Attorney General’s office) found Adams was involved in a contraband smuggling ring linked to an inmate-orchestrated murder plot at the prison. In another case, two guards at Calhoun State Prison tried to smuggle meth and tobacco hidden in Hot Pockets, while a different officer was caught with water bottles refilled with liquid meth, pot, and pills. Such incidents are so frequent that arrests of GDC employees occur on an “almost weekly” basis, ensnaring staff of all ranks from new cadets to lieutenants. Corrupt officers have been caught opening doors for drone drops, warning inmates of upcoming shakedowns, laundering money, and even selling information about prison security.

Systemic factors contribute to this epidemic of misconduct. Georgia’s prisons suffer from severe understaffing and high turnover, creating an environment where corruption can thrive. Many new hires are young, inexperienced, and poorly paid – in some cases “making chump change” – which can make them vulnerable to bribery or coercion by inmate gangs. Training and oversight are often lacking, and prisons in remote areas struggle to recruit qualified personnel. Under these conditions, “as fast as [the] dirty officers are arrested, new ones take their places,” the AJC observed. The result has been a flood of contraband and lawlessness behind bars. For example, one federal bust (“Operation Ghost Busted”) revealed a massive drug trafficking network run by the Ghost Face Gangsters gang across at least 10 Georgia counties, coordinated in part by a young correctional officer who had risen to sergeant before getting caught smuggling meth into the prison.

Not only lower-level staff, but leadership has been implicated in wrongdoing or negligence. In the Smith State Prison case, investigators believe Warden Adams’s corrupt dealings contributed to multiple violent crimes (including at least one murder) ordered from inside the prison. And in Georgia’s highest-security facility – the Special Management Unit (SMU) for the “worst of the worst” inmates – officials spent years defying a court settlement meant to curb abusive solitary confinement conditions (discussed more below). The sheer scope of internal criminal activity is alarming: in a six-year span, hundreds of Georgia correctional officers were arrested on charges ranging from contraband smuggling to extortion, assault, and sexual abuse. Dozens more were quietly fired for misconduct that never led to prosecution. These arrests and scandals paint a picture of a prison system struggling to police itself, where corruption has become entrenched and, at times, even “expected” as part of the job.

Cover-Ups and Lack of Transparency

In a damning 2024 ruling, a federal judge said Georgia prison officials showed “no desire or intention” to implement court-ordered reforms to the SMU and held them in contempt. The judge found officials had even falsified documents to mask their failure to improve inhumane conditions, calling the violations “flagrant.”

Beyond the raw criminality, the GDC’s leadership has repeatedly been accused of misleading authorities and the public to hide the depth of the crisis. An investigation by the AJC found a “pattern of misinformation” emanating from GDC officials – false statements, falsified and backdated records, and data manipulation – all aimed at covering up dysfunction and violence in the prisons. For example, in 2023 the department stopped including preliminary causes of death in its monthly reports on inmate fatalities. This seemingly small reporting change had a big effect: it became nearly impossible to tell how many prisoners were being murdered or dying by suicide, since even obvious homicides (beatings or stabbings) were listed with “no initial finding” on cause of death. The timing was suspicious, as Georgia’s prison homicide rate had spiked to record levels in recent years. GDC Commissioner Tyrone Oliver publicly denied that the prison system was in crisis, even dismissing news reports of undisclosed homicides and rising deaths as “propaganda” in a legislative hearing. Meanwhile, internally the agency was scrambling to obscure the truth.

When federal investigators and courts came knocking, Georgia prison officials stonewalled and deceived them as well. In 2021, the U.S. Department of Justice opened a civil rights investigation into Georgia’s state prisons, citing “unchecked deadly violence” and rampant contraband-fueled crimes. Rather than fully cooperate, the GDC refused to release many of the requested records and restricted federal access to prisons and staff, according to the DOJ’s findings report. Investigators said Georgia’s lack of cooperation made the probe “unnecessarily contentious and lengthy,” forcing DOJ to take the extraordinary step of issuing subpoenas and seeking court orders to obtain basic information. In fact, the DOJ had to sue (through an administrative subpoena enforcement) in federal court in 2022 because GDC stalled for six months on producing records, insisting it would hand over data only if DOJ agreed to a gag order (non-disclosure agreement). A federal judge finally intervened in June 2022, ordering Georgia to comply. Even then, the DOJ reported, GDC delayed and dragged its feet – limiting where investigators could go, when they could visit, and whom they could interview. In some cases, by the time records were handed over (under court supervision), their value was diminished or the information was incomplete. Investigators noted that even as of late 2024, Georgia still had not fully responded to some DOJ requests, despite ultimately turning over 19,000+ documents.

There is evidence that GDC’s evasiveness was deliberate. The DOJ report describes how, in the days just before federal inspectors visited certain prisons, staff rushed to patch up leaking roofs, fix long-broken locks, and apply cosmetic improvements to give a false impression of conditions. And in a separate federal lawsuit over solitary confinement abuses at the SMU, U.S. District Judge Marc Treadwell found in 2024 that GDC officials had essentially tried to run out the clock on a settlement by stalling and lying. For four years, GDC claimed to be complying with court-ordered changes for the SMU while actually doing nothing – “a four-corner offense” to delay until the injunction expired. Judge Treadwell’s patience evaporated when evidence revealed blatant falsehoods: at one point, GDC reported that an inmate (the lead plaintiff in the case) had attended a required out-of-cell therapy session after he was already dead. “To state the obvious: there is no way [he] could have participated… after his death,” the incredulous attorneys wrote, highlighting the agency’s submission of impossible records. In April 2024, the judge issued a contempt order against the state, writing, “The Court has long passed the point where it can assume that even sworn statements from the defendants are truthful.” He noted GDC had shown “no desire or intention” to actually carry out the reforms it agreed to, and he appointed an independent monitor to oversee compliance going forward. The contempt findings included proof that officials falsified logbooks and records to cover up ongoing violations (such as keeping inmates in lockdown nearly 24 hours a day, denying them exercise and education time that the settlement guaranteed). In sum, Georgia’s largest law enforcement agency has repeatedly tried to hide potentially damaging information – whether by omitting public reports of prisoner deaths, downplaying riots and escapes as minor “disturbances,” or defying federal oversight – rather than admit the depth of the problems.

This penchant for secrecy extends to public communications as well. Starting in 2021, the GDC stopped issuing press releases about inmate homicides or escapes, breaking with past transparency. For instance, when a convicted manslaughter offender escaped from a work detail in 2023, the public only learned about it from a county sheriff’s alert; the GDC’s website never posted any notice of the escape. The agency’s official news feed now highlights positive stories – officer promotions, inmate graduation programs, even a new prison menu item – while remaining silent on violence, deaths, and security breaches. Similarly, the Department’s online “contraband arrest” reports have been oddly selective. In 2022, the GDC website listed civilian visitors arrested for smuggling, but omitted at least 44 prison staff arrests for contraband that year. Through mid-2023, the site mentioned only 4 staff arrests, despite internal data (obtained via open records requests) showing 38 staff arrested for contraband in 2023, plus the Smith State Prison warden’s arrest – none of which were publicized online. By contrast, a few years earlier, the department routinely acknowledged dozens of staff arrests in these reports. This trend of tightening information control has alarmed lawmakers and watchdogs. “Is the Department of Corrections being fully transparent with everything that’s going on?” one state senator pointedly asked in an August 2024 hearing. The evidence strongly suggests the answer is no – from records and reports to media disclosures, the GDC’s approach has been to conceal the severity of the prison crisis, until or unless independent investigators pry the truth out.

Whistleblowers and Retaliation

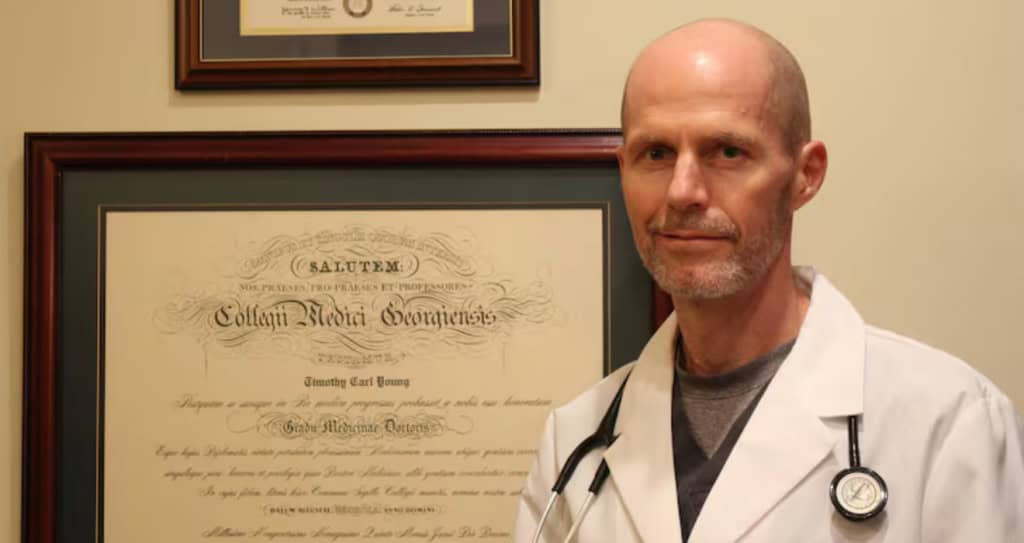

Multiple whistleblowers have tried to expose misconduct in Georgia’s correctional system, only to face retaliation and resistance from officials. One notable case was Dr. Timothy Young, the medical director of the prison hospital in Augusta, GA1.

Dr. Young became alarmed at the dangerously unsanitary and unsafe conditions in the facility – he reported that trash was piling up near an operating room, ceilings were leaking black mold, and insects swarmed during surgeries. He was also concerned that violent inmates weren’t adequately secured when brought in for treatment, and that detainees were suffering serious delays in getting essential care. After repeatedly raising these issues through official channels with no action, Dr. Young eventually leaked information to the press. The AJC published an exposé in 2017 detailing the horrifying conditions and negligence at the medical prison. Rather than thank him, Young says, the authorities ostracized and silenced him: the prison warden refused to take his calls, and higher-ups told Dr. Young “not to put complaints in writing” going forward. He witnessed inmate care deteriorating further and finally resigned in early 2018, ending a 16-year career. Dr. Young filed a whistleblower retaliation lawsuit, which dragged on for years. In 2025, the state quietly settled the case for $300,000 – paid on behalf of the Department of Corrections and Georgia Correctional HealthCare (the prison medical provider) – while denying any wrongdoing. Young said his goal wasn’t money but to force accountability for the needless inmate deaths and suffering he’d witnessed. Tellingly, the Georgia Attorney General’s office (which defended the prison officials) declined to comment on the settlement. The outcome left unclear whether any internal reforms were made, but it vividly illustrated the culture of retaliation that whistleblowers fear: speaking up about abuse or mismanagement can cost a state employee their career.

Another eye-opening whistleblower case involved Captain Sherman Maine, a veteran correctional officer at Valdosta State Prison2 3. Maine objected to a secretive new inmate informant program launched around 2010, in which prison officials were planting informants inside violent prisons and supplying them with contraband cell phones to gather intelligence. To Maine, this off-the-books scheme was “the most dangerous thing you could do” – effectively endorsing illegal cell phone use and putting snitches at mortal risk if their cover blew. In fact, within months of the program’s start, one inmate-informant was nearly killed (stabbed by prisoners who discovered he was a “snitch”), confirming Maine’s fears. Maine himself, as a captain, was ordered to hand out phones to the informants. He refused to do so without a clear, written policy approved by the warden (since giving a phone to an inmate is normally illegal). His superiors brushed off his concerns and reprimanded him for pressing the issue. When an informant was attacked in early 2011, Maine threatened to blow the whistle externally. He wrote a detailed letter about the program to the GDC Commissioner at the time – and was promptly fired in August 2014 for allegedly violating protocol. Maine sued under Georgia’s Whistleblower Act, arguing he was terminated for objecting to an illegal practice. In 2018, a Lowndes County jury sided with Maine, finding that the Department of Corrections had indeed retaliated against him for protected whistleblowing. During the trial, testimony by prison officials revealed just how far the secret informant program had spread: inmates were being used as informers in every one of Georgia’s “Level 5” maximum-security prisons, all under verbal orders with virtually “nothing… in writing” – apparently to avoid any paper trail that open-records requests or discovery could expose. Maine and even a former warden testified that their requests to formalize the policy were denied; they were told the plan “ha[d] been approved all the way up” and to proceed quietly. “You got very few things in writing… Phone calls can be denied. I understood the game,” the retired warden said, describing how the scheme’s secrecy was deliberate. Maine’s warnings were stark: “Every stabbing becomes suspect. We won’t know who’s an informant or not. They’re going to get someone killed, if they haven’t already.” Indeed, the full extent of violence or deaths related to the informant program remains unknown to this day. Despite the jury verdict in Maine’s favor and the risks laid bare, Georgia’s corrections higher-ups acknowledged in court that the informant program was still ongoing as of 2018 – essentially unchanged. The GDC declined to comment at the time due to the litigation, and the case later entered a sealed damages phase. The Maine saga reveals a troubling mindset at GDC: whistleblowers who raise ethical or safety concerns are seen as threats, and dangerous practices might be hushed up rather than fixed. It also illustrates an area where the Department and possibly the Attorney General’s office (which defends the agency in court) were willing to bend or break rules, so long as it was kept “off the books.”

Conduct of the Attorney General’s Office

The Georgia Attorney General’s office has a hand in many of these matters – it serves as the state’s lawyer, defending the GDC in lawsuits and representing Georgia’s interests in court. As such, the AG’s conduct (and misconduct) is an integral part of this story. Critics suggest a pattern of circling the wagons to protect state agencies (and political allies) instead of championing accountability. For instance, in the DOJ’s prisons investigation, it was attorneys from the state (ultimately answering to the Attorney General) who fought the subpoenas and demanded a nondisclosure agreement before releasing records. The pushback against federal oversight – which DOJ described diplomatically as “contentious” – was not just the prison officials’ doing; it was a legal strategy presumably guided by the AG’s office. The DOJ’s final report noted that GDC only began substantially complying in mid-2023 after DOJ “sought and obtained court enforcement” of its subpoena. In other words, Georgia’s lawyers had to be dragged into obeying a lawful inquiry. Even then, the state continued to object to and delay certain document productions, prompting DOJ to remark that Georgia missed chances to correct the record and that some requests (from a 2022 subpoena) were still outstanding in late 2024. It is highly unusual for a state government to so stiff-arm a federal civil-rights probe; the implication is that the AG’s team was more interested in shielding the GDC from embarrassment or liability than in full transparency. Similarly, in the SMU contempt case, the “defendants” making false assurances to the federal judge included the agency’s leadership and by extension their counsel. While the court documents fault prison officials directly, it’s worth noting that state attorneys filed sworn statements that turned out to be false or misleading in that case. This raises questions about the AG’s office’s role – were they misled by their client, or complicit in presenting a rosier picture to the court? Neither scenario inspires confidence. U.S. District Judge Treadwell’s blunt words (that he can no longer assume even sworn statements from the state are truthful) cast a shadow not just on the GDC but on the lawyers representing it.

The Attorney General’s office has also been involved in other controversies beyond the prison walls. One prominent example involves evidence suppression and wrongful convictions. Georgia has seen a series of exonerations in recent years – cases where men spent decades in prison for crimes they didn’t commit, only to be freed after new evidence came to light. Often in these cases, the AG’s office resisted the inmates’ appeals and post-conviction relief, even as evidence of innocence or official misconduct mounted. A case in point is Joey Watkins, a Georgia man convicted of murder in 2001. Watkins always maintained his innocence, and eventually investigative journalists and attorneys (from the Georgia Innocence Project) unearthed shocking irregularities: a juror had conducted an unauthorized “drive test” experiment during deliberations, and key evidence had been withheld from Watkins’s defense at trial. In late 2022, the Georgia Supreme Court unanimously threw out Watkins’s conviction, citing the juror’s misconduct and other due process violations. Yet even after “clear evidence of innocence and misconduct” emerged, the Georgia Attorney General continued to fight to keep Joey Watkins in prison. The AG’s team appealed and delayed wherever possible throughout the habeas process. Watkins was finally exonerated and released in 2023 – after losing 22 years of his life behind bars – and a state lawmaker noted that “information [was] withheld from the defense” in his case, highlighting how the system failed him. Observers of the Watkins case and others like it (e.g. the exonerations of Lee Clark, Joshua Storey, and others) have criticized the Attorney General’s office for a “win at all costs” mentality – defaulting to oppose retrials or new evidence hearings to uphold convictions, rather than proactively addressing potential injustices. In Watkins’s situation, it took podcasts, media attention, and external pressure to get the state to relent. As Watkins himself told legislators after his release, “When you’re wrong in the state of Georgia, and they know you’re wrong, you will get punished to the full extent… But when you’re not wrong… please do the same thing. Help us.” His plea underscores a feeling that Georgia’s leadership (legal and political) has been slow to correct injustices – unless forced.

Allegations have also arisen that the AG’s office and state leadership engage in politically motivated interference in certain legal matters. A recent flashpoint is a Georgia law passed in 2023, championed by Attorney General Chris Carr, that creates a new “Prosecuting Attorneys Oversight Commission.” This state-level commission has sweeping power to investigate and even remove elected district attorneys for an array of reasons – from actual misconduct to “failure to prosecute” certain types of crimes. Carr and supporters (mostly Republican lawmakers) argued it’s needed to hold rogue prosecutors accountable, pointing to a high-profile case where a DA was charged with mishandling the Ahmaud Arbery murder (indeed, AG Carr’s office successfully indicted Brunswick DA Jackie Johnson in 2021 for allegedly shielding Arbery’s killers). However, the new law’s breadth and timing raised red flags among many observers. It came as a response to conservative frustrations with some reform-minded or “progressive” district attorneys – for example, DAs who decline to prosecute low-level drug offenses or, notably, Fulton County DA Fani Willis, who in 2023 brought an election-interference RICO case against former President Donald Trump and his allies. Willis and several other DAs have blasted the oversight commission as a political tool. Willis called the law a “direct threat” to the independence of prosecutors elected by their communities, and “an overreaction” by those who simply don’t like certain case outcomes.

Civil rights groups and four Georgia DAs (from both parties) filed a lawsuit to block the commission, arguing it unconstitutionally undercuts voters’ choices and could be weaponized for partisan retaliation. Despite this, AG Chris Carr has vowed to enforce the law aggressively, warning that DAs who “embrace the progressive movement… of refusing to enforce the law” are committing a “dereliction of duty” and “will be held accountable.” This rhetoric – singling out DAs with policies he disagrees with – has amplified fears that the AG’s office is veering into political retaliation. The law could theoretically be used to target someone like Willis (for pursuing a politically sensitive prosecution) or Athens DA Deborah Gonzalez (whom Republicans criticize for not pursuing certain cases). In effect, the Attorney General now oversees a mechanism to second-guess and punish other elected legal officials, which is virtually unprecedented in Georgia. Carr defends it as analogous to oversight boards for judges and police, but detractors note those bodies address clear ethical violations, not policy disagreements. The clash over this commission reflects a larger pattern: the Georgia AG’s office aligning with ruling-party politics and power, sometimes at the expense of independent justice. Whether it’s joining multi-state lawsuits on hot-button national issues, defending controversial state laws (like election restrictions) in court, or flexing new powers over local prosecutors, the office has been at the center of debates about the proper balance between enforcing laws and pursuing fairness. And when the AG’s actions are viewed alongside the Corrections Department’s troubles, a common thread appears – an instinct to shield the “system” against criticism, whistleblowers, or outside scrutiny, even if that means fighting transparency or accountability.

Conclusion

From Georgia’s prison cellblocks to its halls of justice, a troubling picture has emerged of entrenched misconduct and resistance to oversight. Inside the GDC, corruption has festered: officers and officials involved in drug smuggling, extortion, and cover-ups have endangered not only inmates but the public at large. Rather than confront these problems openly, the Department’s leadership chose to obscure them – withholding information about inmate deaths, lying to legislators and judges, and stonewalling federal investigators. When brave insiders like Dr. Young or Captain Maine tried to shine a light, they were met with retaliation and denial. Meanwhile, the state’s top legal office – the Attorney General’s – has often appeared more intent on defending the machinery of state government than on reforming it. Whether by dragging its feet on releasing damning records, dismissing credible claims of wrongful convictions, or asserting new powers that could be used punitively against independent prosecutors, the AG’s office has contributed to a culture of opacity and impunity in Georgia’s justice system.

However, the mounting evidence compiled by journalists, whistleblowers, and federal authorities is becoming too large to ignore. Judges have started to sanction Georgia officials for dishonesty. The U.S. Department of Justice has explicitly found that Georgia’s prisons violate inmates’ constitutional rights by failing to protect them from harm – a scathing indictment of the state’s management. And public outrage is growing as stories of egregious abuses and cover-ups come to light. All of this pressure is building towards a simple reality: meaningful change is necessary. Experts say it will require strong, ethical leadership and robust oversight to break the cycle – from cleaning up corruption within prison ranks to changing incentives in the AG’s office to prioritize justice over “wins.” Some steps are already underway (for example, a federal monitor in the SMU case, and legislation to compensate the wrongfully convicted was recently signed into law), but systemic reform remains elusive.

Ultimately, restoring trust will demand that Georgia’s institutions embrace transparency and accountability rather than evade it.

The pattern of misconduct outlined here – spanning prison guards running criminal enterprises, wardens and lawyers falsifying the record, and officials retaliating against truth-tellers – is a wake-up call. It asks whether those in power will continue to cover up the truth or finally confront it, and ensure that the state’s justice system actually delivers justice, both inside prison walls and beyond.

What You Can Do: Take Action Against the Cover-Up

This is more than corruption. It’s an organized assault on truth, accountability, and justice—and it’s happening with your tax dollars. We cannot let these systems continue to harm, silence, and bury the people caught inside them.

Here’s how you can help right now:

✅ Use ImpactJustice.AI

In under 2 minutes, you can send powerful, AI-written messages to:

- Georgia legislators

- Media outlets

- oversight bodies demanding investigations, legislative hearings, and prison population reduction

📬 Visit: https://ImpactJustice.AI

📞 Contact Your State Legislators

Find your Georgia State Representative and Senator:

🔍 https://openstates.org/find_your_legislator/

Then:

- Call and demand that they take action to investigate the GDC and Attorney General’s Office.

- Write or email them using your own words or by copying points from this article.

- Ask them: “What are you doing to stop the corruption and abuse in Georgia’s prisons?”

📢 Share This Exposé

The more people who read this, the harder it is for the state to hide. Share the full article with your networks:

🔗 https://gps.press/expose-how-georgias-justice-system-functions-as-a-criminal-enterprise/

Post it on:

- Facebook groups

- Telegram chats

- Twitter/X

- Reddit forums

- And anywhere people are organizing for justice

🛑 Silence protects the powerful. Speaking out protects the people.

Use your voice. Expose the truth. Demand accountability—because justice doesn’t end with sentencing. It begins with how we treat people after.

End Notes / Sources

🔗 Atlanta Journal‑Constitution (AJC) Investigations

• Investigation into over 425 GDC staff arrests since 2018:

• Follow-up reporting on contraband smuggling and drone use:

Smith State Prison Warden Arrest

• Official GDC press release:

https://gdc.georgia.gov/press-releases/2023-02-08/smith-state-prison-warden-terminated

• Local reporting by WTOC/other outlets on RICO arrest:

Whistleblower & Prison Medical Neglect

• AJC report on Dr. Timothy Young’s whistleblower retaliation:

• Federal judge’s ruling allowing Dr. Young’s case to proceed:

• AP News on settlement involving Dr. Young and GDC:

https://apnews.com/article/lawsuits-georgia-8a4ba85794d25c5c610cfc8c784975bc

Wider Reporting & Data

• AJC coverage of GDC withholding homicide and suicide data:

• AJC follow-up on untested contraband evidence and dropped cases:

https://www.ajc.com/news/2025/06/smuggling-cases-at-georgia-prison-fizzle-drugs-were-never-tested

Federal Court and DOJ Oversight

• DOJ report subpoenaing records & finding constitutional violations:

(Direct DOJ link to October 2024 report)

https://www.justice.gov/d9/2024-09/findings_report_-_investigation_of_georgia_prisons.pdf

Local Media & Eyewitness Reporting

• AP News on the RICO indictment of Warden Adams:

https://apnews.com/article/e5b55d2aab37125b8d42cdacc1335a62

• WRDW (AP pick-up) on 360 GDC staff arrests since 2018:

https://www.wrdw.com/2023/09/26/360-ga-prison-guards-arrested-smuggling-since-2018

📚

Further Reading from Georgia Prisoners’ Speak (GPS)

Explore more reporting that exposes the corruption, brutality, and constitutional failures within Georgia’s justice system:

🔗 Lethal Negligence: The Hidden Death Toll in Georgia’s Prisons

Reveals how the Georgia Department of Corrections (GDC) covers up inmate deaths, delays autopsies, and leaves families without answers.

🔗 The Felon Train: How Georgia Turns Citizens into Convicts

Georgia’s justice system isn’t about justice—it’s about control. It’s about turning everyday people into lifelong convicts, feeding a machine built to profit from mass incarceration. People like Wayne Key, who spent a decade behind bars—not for violence, not for endangering others, but for the same substances now sold legally on every street corner.

🔗 In and Out: The Lives Destroyed by the GDC

Details the human toll of Georgia’s failed rehabilitation system, where inmates cycle through trauma without support.

🔗 From Kangaroo Courts to Chaos: Georgias Prison Crisis

Examines the abuse of disciplinary reports (DRs) and misclassification, often used to silence or punish prisoners arbitrarily.

🔗 Unconstitutional: Georgia’s Extrajudicial Punishment

Argues that the conditions inside Georgia prisons violate the Eighth Amendment and extend punishment far beyond what judges impose.

🔗 A Simple Message for the GDC

Outlines urgent reforms needed to reduce violence, improve transparency, and hold Georgia prison officials accountable.

🔗 Fixing Georgia’s Parole System: The Ultimate Plan for Justice

Breaks down how the parole board’s opaque decisions exacerbate overcrowding and hopelessness inside GDC facilities.

🔗 A Second Chance for Georgia: Fixing Parole With the Reform It Desperately Needs

Presents a legislative roadmap—the Second Chance Parole Reform Act—for building a transparent, fair, and life-saving parole system.

- https://www.prisonlegalnews.org/news/2018/sep/3/georgia-medical-prison-rife-dysfunction-abuse-and-dilapidated-conditions/[↩]

- https://www.ajc.com/news/crime–law/secret-informant-program-putting-georgia-inmates-risk/BqOXbNWUehXG2jpXN7fviO/[↩]

- https://valdostadailytimes.com/2018/10/23/former-valdosta-prison-guard-wins-lawsuit/[↩]

2 thoughts on “Exposé: How Georgia’s Justice System Functions as a Criminal Enterprise”