Estimated reading time: 40 minutes

The U.S. Department of Justice documented 142 homicides in Georgia prisons from 2018 to 2023—a 95.8% increase from the first three-year period to the second. In 2023 alone, Georgia set a record with 35 prison homicides. The state’s prison homicide rate of 34 per 100,000 incarcerated people nearly triples the national average of 12 per 100,000.

But the crisis has accelerated dramatically. Georgia Prisoners’ Speak documented 100 homicides in Georgia prisons in 2024—nearly triple the previous year’s record. The official GDC count for 2024, as reported by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, lists only 66 homicides. That’s 34 deaths the state either misclassified or concealed—consistent with the pattern of falsified reporting that led Federal Judge Marc Treadwell to hold the GDC in contempt, stating bluntly: “The Court has long passed the point where it can assume that even sworn statements from the defendants are truthful.”

These aren’t random acts of violence. They’re the predictable, inevitable consequences of deliberate Georgia Department of Corrections policies that create an economic crisis so severe that survival itself requires breaking rules, stealing from the system, and stealing from each other. When 14,000+ validated gang members control housing assignments and contraband distribution in a system where correctional officer vacancy rates reach 60%, the violence isn’t a failure of policy—it’s the policy working exactly as designed.

To understand why Georgia’s prisons have become killing fields, you must first understand what survival costs when the state pays you nothing, feeds you inadequately, and charges you everything.

The Impossible Equation: Zero Wages, Starvation Rations, Premium Prices

Georgia stands among only seven states paying prisoners absolutely nothing for their labor. Not cents per hour. Not dollars per day. Zero compensation regardless of hours worked or tasks performed. Approximately 9,000 Georgia prisoners work annually for cities and counties, maintain 14,150 acres of prison farms providing 43% of system food, manufacture goods in 18 factories, and conduct public works—all for free. The Department of Corrections operates on a $1.5 billion annual budget while extracting this unpaid labor, directly offsetting operational costs the state would otherwise bear.

But paying nothing proves only half the exploitation. As Georgia Prisoners’ Speak documented in “Starved and Silenced: The Hidden Crisis Inside Georgia Prisons,” the GDC feeds inmates on 1,200-1,400 calories daily—half the 2,500-2,800 calories adult males require. Former kitchen workers describe “shaking the spoon”—deliberately shorting portions to stay under budget and earn bonuses. Inmates report losing 30-50 pounds, eating toothpaste to calm hunger, and receiving spoiled food contaminated with mold. One mother described her son as looking “like he belongs in a concentration camp—skinny, pale, dark circles under his eyes.”

When inadequate food forces prisoners to commissary, they encounter the systematic price gouging GPS exposed in “Georgia’s Prison Commissary Extortion.” Ramen costs $0.90 (versus $0.20 true institutional cost). Ibuprofen costs $4.00 (versus $0.34 wholesale). Soap carries markups reaching 1,812% over wholesale. The state extracted $18.76 million in commissary profit in 2024, then implemented 30% price increases in November 2025, raising annual extraction to an estimated $60+ million.

This creates an equation with no legitimate solution:

You cannot earn money through work. The food provided is insufficient to survive. The only place to buy supplemental food charges prices impossible to afford without income. What would you do?

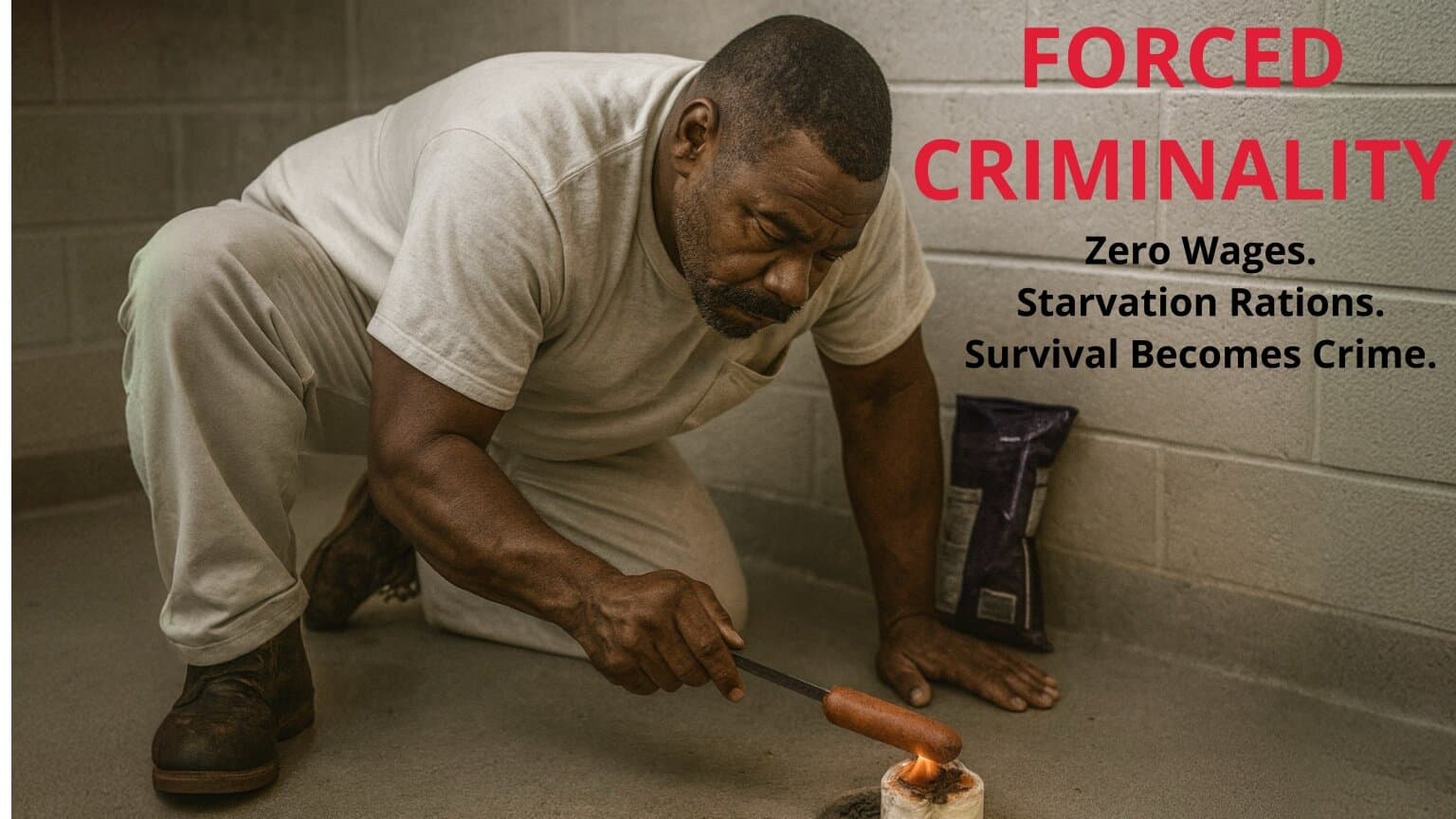

The answer appears in a photograph that has circulated among Georgia prison families—a man hunched over a makeshift flame on a bathroom floor, cooking a piece of sausage while another prisoner stands lookout.

When Survival Becomes Crime: Cooking on Bathroom Floors

“Inside Georgia’s prisons, survival becomes a full-time job. This photo shows me cooking a piece of sausage over a makeshift flame on a bathroom floor—not because I wanted to, but because the cafeteria food was unsafe and the hallways were filled with gang violence. Sometimes the only way to eat was to stay in the dorm, stay hidden, and take the risk. Another incarcerated man stood lookout so I wouldn’t get written up. That’s what survival looks like inside a system that’s supposed to ‘rehabilitate.’ When you’re wrongfully convicted, you’re not just fighting your case—you’re fighting to stay alive.”

The man who cooked that meal violated prison rules. He possessed contraband. He created a fire hazard. He required another prisoner to serve as a lookout, making that person complicit. Someone took a photo with a contraband phone. Each person involved risked disciplinary action that could extend their sentences by parole denial or even new charges, cost them privileges, or land them in segregation.

But the alternatives? Eat unsafe cafeteria food that GPS documented as contaminated, spoiled, and nutritionally inadequate. Navigate hallways controlled by gangs the DOJ found operating with impunity due to catastrophic understaffing. Pay commissary prices that consume any money families can scrape together—families already missing a wage earner and struggling with their own survival.

This isn’t a prisoner choosing criminality. This is the Georgia Department of Corrections forcing criminality as the only survival strategy.

The pattern repeats across every aspect of prison life. When the state provides nothing—or provides it inadequately while charging exorbitantly for alternatives—prisoners must break rules to meet basic human needs. The underground economy that emerges isn’t about greed or criminal character. It’s about not starving. Not going without soap. Not suffering untreated illness. Not being beaten by gangs who control resources the state refuses to provide.

And when that underground economy operates without legitimate alternatives, it generates the violence the DOJ documented with devastating precision.

The Kitchen: Where Survival Theft Begins

Food service assignments represent the most coveted prison jobs not because they teach marketable skills, but because they provide access to the one commodity everyone desperately needs: food. The GDC claims kitchen work constitutes “job training” and issues certificates from local technical colleges. But as one former worker explained, the reality is quite different: “doing laundry with no pay is not job training for anything. Neither is maintenance or kitchen work where most of the inmate staff is there to spoon food on to trays or clean the pots and pans.”

The real purpose of kitchen jobs is theft. Not theft driven by greed, but theft driven by hunger—both the worker’s own and the hunger they can profit from by selling to other starving prisoners.

“I would bring back food every day. I sold it so I could eat something that was more appetizing than what they served in the chow hall.”

“I got fired last week from the kitchen for bring back some butter to sell. I know I wasn’t supposed to, but we have to eat.”

“I sell kitchen food to my regular customers so I can smoke. A cigarette costs 4 soups here, but it calms my nerves.”

These aren’t professional criminals bragging about scores. These are people explaining survival strategies in an impossible situation. The first needs edible food. The second needs to eat. The third needs something to manage the psychological torture of confinement—and cigarettes cost four ramen soups ($3.60 at current prices), meaning smoking requires continuous income in a system that pays nothing.

But survival theft operates at scales far beyond individual meals. One former warehouse worker described an operation of stunning scope: “I worked in the kitchen warehouse for 5 years at my last camp. I shipped out a laundry cart of sugar, tomato sauce, grits and cornmeal every day on the weekends, and sometimes during the week. I could make a thousand dollars a day, but I had to share that with a couple of the ladies that worked there.”

A thousand dollars a day. In a system where inmates earn zero wages, where families struggle to send $50 twice monthly for commissary, someone was generating more income from theft than many working Georgians earn legitimately. The scale reveals both the desperation of the market—people willing to pay that much for basic food—and the sophistication of operations that develop when legitimate survival paths don’t exist.

The corruption extends to staff. One former warehouse worker described a year-long scheme where the food services director operated a catering business using diverted prison food: “The food services director had a catering business and she would pay me to divert certain food items coming into the prison. I put it in a special freezer where we held it until the truck was empty. Then we loaded the truck back up and I’m told the driver took it to her house. We did this every week for a year until I was transferred. She paid me in chicken nuggets that I would resell in the dorm for $25 a plate. The dorm loved me.”

The director stole from the state to operate a private business. She paid an inmate in stolen food. That inmate sold the food to other inmates at $25 per plate—roughly 28 ramen soups’ worth at current commissary prices, or what a family might send in a month. Everyone in the chain was stealing. Everyone was breaking rules. And the dorm “loved” the person providing food that was edible and sufficient, even at premium prices.

This is what forced criminality looks like at scale.

COVID and the Brutal Mathematics of Scarcity

If chronic hunger creates underground food economies, acute scarcity creates violence. During COVID, when Georgia prisons eliminated chow hall service and implemented sack lunches, the system’s brutality became undeniable.

One prisoner described what happened:

“COVID turned prison into a ghost of what it already was. No chow hall. No hot trays. No dignity. Just three brown paper sack lunches a day—if you were lucky. Two slices of sticky bread. A slab of mystery meat. A handful of soggy carrot coins. A juice that tasted like regret. That was survival.”

When the already-inadequate became even worse, something had to give. The COVID sack lunch system relied on prisoner trustees to distribute meals. And when people are hungry, they notice everything:

“We started noticing sacks missing. Two here. Three there. Never enough to feed everyone. At first we blamed the kitchen. Then the packing crew. Then each other. But eventually the truth revealed itself: A hand dipping low… A shirt puffing out… A man walking off with two sacks instead of one.”

The thief was stealing from fellow prisoners—men already surviving on rations insufficient to sustain life. In prison’s moral economy, this crosses a line that stealing from the state does not:

“In prison, that’s not selfishness—that’s violence. One night, they caught him in the act. Not the officers—us. No yelling. No threats. Just a few men stepping forward and grabbing him by the shirt. They took him to the back by the showers—the blind spot the cameras can’t reach. There were no debates. No explanations. No defense. Just fists, silence, and the brutal math of survival.”

The beating wasn’t about justice—it was about enforcement in a system where no legitimate authority addresses survival needs. The quote that emerged from that violence captures the moral framework operating in Georgia’s prisons:

“Steal from the state all you want. But steal from starving men? That’s how you get fed to the floor.”

The next morning, every sack was accounted for. The violence had served its purpose—establishing and enforcing rules that the state’s absence makes necessary.

This is the violence Georgia’s policies create. Not random brutality, but calculated enforcement of survival ethics in a system designed to starve.

The Alcohol Economy: Risk, Revenue, and Rationalization

When legitimate survival requires theft, some prisoners expand into production. The prison alcohol economy represents perhaps the most sophisticated example of forced entrepreneurship, requiring supply chain development, hidden production facilities, distribution networks, and constant risk management.

The economics prove compelling enough to justify extraordinary risks. One producer explained: “I’ve known people to make $3-4000 in a single weekend of making distilled alcohol.”

Three to four thousand dollars. In a system where zero wages means zero legitimate income, this represents years of what families might send. It also represents what the underground economy will pay for a product that serves multiple purposes: stress relief in an environment of perpetual trauma, a currency more stable than ramen, and a coping mechanism for people surviving conditions the DOJ found constitutionally inadequate.

The production process requires stolen materials. Sugar bags can sell for $200 each. Large cans of tomato paste or sauce fetch $50-75. These ingredients come from kitchen workers stealing them, often in massive quantities, to supply alcohol producers. The production itself requires ingenuity and constant vigilance:

“I used to make buck and even distilled it. I made a lot of money, but it was a lot of work and I was always on edge every time the cert team would come in the dorm or even in front of the dorm.”

The “buck” (fermented fruit or sugar water) sits for weeks, creating evidence that can result in criminal charges. The distillation process uses a “bug”—two metal plates separated by an insulator, plugged into electrical outlets to heat the buck to boiling, with vapors condensing in trash bags. The equipment must be hidden. The production schedule must account for shakedowns. The operation requires multiple people, creating dependencies and vulnerabilities.

The final product—distilled spirits in 20-ounce soda bottles—sells for $50-150, often on the high end of that range. The producers rationalize the risk and the rules broken with reasoning that reveals the system’s psychological impact:

“I love making clear. I make good money and it helps the community. A lot of people need alcohol to relax—prison is nothing but stress.”

“Helps the community.” “People need alcohol to relax.” The language of public service applied to an illegal enterprise driven by forced survival strategies in a deliberately stressful environment. This is what happens when the state creates unbearable conditions and provides no legitimate coping mechanisms—people create their own, breaking rules to meet needs the system refuses to address.

When Legitimate Hustles Fail: The Criminalization of Survival Itself

Not everyone steals or makes alcohol. Some prisoners attempt to create quasi-legitimate businesses within the underground economy—repairing electronics, reselling commissary items, providing services. One prisoner who repairs items for others described his business as “chronic”—constant work that “just helps him have food to eat without calling home asking for help from family.” The motivation isn’t profit but survival while protecting family members already burdened by zero wages and commissary exploitation.

Another learned the resale business “by watching the people in prison buy and trade” and picking “up on the needs of others”—becoming an amateur economist out of necessity, studying supply and demand in a captive market with zero legitimate income.

But even these attempts at lawful survival face an insurmountable economic problem: “Frugal spending dictates sales.” When no one is paid wages and everyone is struggling, even minor services become unaffordable. The handyman is “upset about his business because it’s a constant job of fixing people stuff” and “most people don’t want to pay the price he’s charging them to fix things.”

Then comes the policy that transforms economic failure into absolute impossibility: Georgia Department of Corrections rules explicitly prohibit inmates from trading anything of value with another inmate.

Read that again. The handyman fixing someone’s radio for a soup? Rule violation subject to disciplinary action. The reseller trading commissary items? Rule violation. Washing someone’s clothes for ramen? Rule violation. Every single economic transaction between prisoners—no matter how benign, no matter how necessary—constitutes a crime under GDC policy.

The GDC hasn’t simply failed to provide adequate wages or survival resources. It has systematically criminalized every possible alternative. There is no “quasi-legitimate” business option. There is no lawful hustle. There is no legal economic activity beyond what the state directly provides. And what the state provides is deliberately insufficient: zero wages, starvation-level nutrition documented at 1,200-1,400 calories daily, and commissary prices marked up 400-900% over legitimate costs.

The mathematics are perfect in their cruelty: You cannot earn money legally because the state pays nothing. You cannot survive on what’s provided because it’s deliberately inadequate. You cannot buy what you need because prices are designed to extract maximum wealth from families. And you cannot trade, barter, or create any economic alternative because GDC policy criminalizes all of it.

This is forced criminality in its purest form—not people choosing crime, but crime being the only option the state permits. When “legitimate” survival strategies are illegal and fail economically, and when starvation is the alternative, the choice isn’t whether to break rules. The choice is which rules to break and whether you’ll get caught.

The answer, inevitably, is theft—from the kitchen, from the warehouse, from other inmates. And theft generates the debt, competition, and scarcity enforcement that produces the violence the DOJ documented with 142 homicides and a 95.8% increase in killing between periods.

Georgia didn’t fail to prevent this violence. Georgia designed the conditions that make it inevitable.

The Haves and the Have-Nots: How Money From Outside Forces Universal Criminality

The underground economy creates a rigid class system within Georgia’s prisons. Those receiving money from family—the “haves”—occupy a different world than those without outside support. They can afford commissary prices, can buy extra food, can purchase services. But wealth doesn’t exempt them from forced criminality. It simply changes the crimes they commit.

Every transaction in the underground economy has two parties: the seller and the buyer. When a kitchen worker sells stolen butter, someone buys it. When someone produces alcohol for $150 per bottle, someone pays. When the handyman repairs electronics for soup, someone trades for that soup. The “haves” sustain the entire underground economy through their purchases—and every purchase violates the same GDC rule prohibiting inmates from trading anything of value.

The prisoner buying stolen chicken nuggets for $25 per plate is as guilty of rule violation as the warehouse worker who diverted them. The inmate paying for personalized laundry service breaks the same policy as the laundry worker providing it. The man purchasing distilled alcohol funds the theft of sugar and tomato paste from the kitchen, making him complicit in that theft even if he never entered the kitchen himself.

This complicity isn’t moral failing—it’s forced necessity. The “haves” face the same inadequate meals, the same spoiled food, the same nutritional crisis documented at 1,200-1,400 calories daily. Having money from family doesn’t make prison food edible or adequate. It simply means they can afford to supplement it by purchasing from the underground economy that theft creates.

But their participation as buyers creates the demand that drives the supply. Kitchen workers steal because they know the “haves” will pay for real food. Alcohol producers risk everything because they know buyers exist who need stress relief badly enough to pay $150 for a 20-ounce bottle. The hustlers persist despite economic struggles because some prisoners can afford to pay, even if most cannot.

The result is a prison class system that mirrors the poverty dynamics outside. Those with outside support can eat adequately, manage stress, maintain hygiene. Those without support must steal, join gangs, or slowly deteriorate from malnutrition and neglect. Wealth determines not just comfort but survival—and creates resentment, tension, and additional violence between the haves and have-nots competing for limited resources.

Yet both groups—the supported and the unsupported, the buyers and the sellers—become criminals under GDC policy. The trading prohibition criminalizes everyone who participates in economic transactions, regardless of whether they steal or simply purchase. A prisoner whose elderly mother on disability sends $100 monthly becomes a rule violator the moment he trades soup for clean laundry. A man whose wife works two jobs to send commissary money commits a crime when he buys extra food from a kitchen worker.

The genius of Georgia’s system is that it forces universal criminality. There is no way to survive without breaking rules. The desperately poor must steal. Those with modest support must trade. Even the relatively wealthy must purchase from underground markets because legitimate options are deliberately inadequate or don’t exist—bandaids can’t be bought in commissary, adequate food isn’t served in the chow hall, stress relief isn’t provided through programming.

When 100% of the prison population must break rules to survive, rehabilitation becomes impossible by definition. You cannot teach respect for law while forcing universal lawbreaking. You cannot instill legitimate values while criminalizing every legitimate transaction. You cannot prepare people for law-abiding reentry while ensuring their daily survival requires crime.

The question isn’t whether Georgia’s prisoners are criminals. The question is whether any human being could survive in these conditions without becoming one.

Gang Control: The Economics of Terror

The DOJ found 14,000+ validated gang members in Georgia’s prison system. These aren’t social clubs. They’re economic enterprises operating in a vacuum created by state neglect, providing governance, resource distribution, and violent enforcement where the GDC refuses or cannot.

Gangs profit from controlling what the state fails to adequately provide. In dorms where one gang achieves dominance, every basic necessity becomes a revenue source:

Shower access: One ramen soup ($0.90 at current commissary prices)

Room assignment: A two-man cell in a dorm where others sleep three to a cell can cost $500. When gangs want single cells, they kick out roommates who must then sleep on the dayroom floor—“thrown to the streets” in prison parlance. Photographs obtained by GPS show men sleeping on dayroom floors, without access to cells, without privacy, without even reliable bathroom access.

This last detail creates another layer of degradation and violence. Men kicked from cells have no place to use toilets overnight. They must defecate in showers. The gang members who kicked them out then become enraged about shower conditions and administer beatings for the problem they created.

The testimony about gang economics is limited, but the limitation itself proves revealing. When asked about gang control of resources, multiple sources provided the same response: “No one is willing to talk about gang control for fear of pain.”

The fear is the evidence. The silence proves the violence.

The DOJ documented this reality with devastating clarity. Gangs control housing assignments. They control extortion. They control contraband distribution. They operate with impunity because the correctional officer vacancy rate reached 52.5% systemwide in 2023, peaking at 60% in April. Officers regularly supervise two buildings simultaneously—nearly 400 beds—and housing units frequently remain completely unsupervised. From 2022-2024, Georgia authorities confiscated 37,000 contraband devices, averaging 1,300 found monthly—a rate suggesting tens of thousands in circulation at any time.

Gangs fill the governance void the state creates through deliberate understaffing. They provide order—violent, extortionate order, but order nonetheless. David Skarbek’s research in the Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization explains that “prison gangs provide governance institutions that allow illicit markets to flourish. They adjudicate disputes and protect property rights.” They don’t create chaos—they orchestrate violence so it becomes “relatively less disruptive” to their economic interests.

Georgia’s gangs profit from the desperation zero wages create. Every prisoner needing food, soap, or stress relief becomes a potential customer. Every rule the state doesn’t enforce becomes an opportunity for gang enforcement with gang fees. The 14,000+ gang members aren’t a failure of corrections—they’re the inevitable result of creating a system where survival requires participation in underground economies that gangs control.

The Medical Underground: Saving Lives While Breaking Rules

The sophistication of prison economics extends even to healthcare. When the state provides inadequate medical care—GPS’s starvation article documented that sick call requests often take weeks—prisoners create their own parallel medical system, stocked with stolen supplies and staffed by untrained “medics.”

Bandaids can’t be bought in commissary, so they must be stolen from medical. But bandaids serve purposes beyond minor cuts:

“I keep a supply of bandages of several types including super glue, to help someone who gets stabbed. I’ve never actually saved a life, but I definitely helped someone from losing a lot of blood or getting a serious infection.”

The stab wound supplies—sutures, butterfly strips, antiseptics, large bandages—serve dual purposes. First, they literally save lives when medical staff might not arrive for hours despite life-threatening injuries. Second, they hide violence from administration:

“We have illegal medical supplies in our dorm. It’s to save lives, and also because if someone goes to medical with a stab wound, the dorm will be locked down and shook down. The ones doing the stabbing never get punished even though there are cameras.”

Read that again: “The ones doing the stabbing never get punished even though there are cameras.”

Prisoners hide violence to avoid collective punishment. They treat stab wounds illegally to protect themselves from administration retaliation while the actual stabbers face no consequences. This inverts every principle of rehabilitation, creating incentives to conceal crimes, treat injuries without training, and maintain illegal medical supplies.

The underground medical economy extends to pharmaceuticals. Inmates prescribed antibiotics often take just enough to recover, then sell the remainder to others who want to stockpile them. Why? Because getting seen in medical “can take as long as a week” and “by that time you have suffered through most of the illness, and quite frankly you could even die of the illness and become a statistic in the ‘died of natural causes’ category.”

People hoard stolen antibiotics because the legitimate medical system is so inadequate that waiting for treatment might kill them. This is forced criminality extending even to healthcare.

The most advanced contraband operations use drones. A drone can cost $10,000 and requires someone outside to operate it. Staff must be bribed to ignore it. Each drop can cost $5,000. Because drones carry only 4-10 pounds, only the highest-value items justify the economics: tobacco, marijuana, methamphetamine, and increasingly, medical supplies.

Recent photographs of drone packages show cold/flu medications and bandages alongside drugs. The legitimate and the illegal arrive together because the state provides neither adequately. When bandaids require drone smuggling because commissary doesn’t sell them and medical won’t provide them, the system has created conditions where literally every aspect of survival requires breaking rules.

Violence Over Debt and Theft: The Enforcement Mechanism

Underground economies require enforcement mechanisms. Without courts, contracts, or legal recourse, violence becomes the collections department.

Drug debts generate particularly brutal enforcement. When people become addicted to methamphetamine, fentanyl, or synthetic strips (paper soaked in drugs, easily mailed), dealers often extend credit knowing they’re creating risk. They do it anyway because possessing drugs means risking loss to shakedowns, so moving product quickly—even on credit to unreliable customers—beats keeping inventory. When addicted customers can’t get family to send money via CashApp or Chime to the dealer’s outside contacts, examples must be made:

“The beatings are generally harsh, sometimes fatal (it would be very rare that weapons would be involved here, the dealers need returning customers, not dead bodies).”

Sometimes fatal. These aren’t the homicides the DOJ counted—those are the ones that couldn’t be hidden. But even “harsh beatings” that don’t quite kill still send messages about debt consequences in an economy where zero wages mean zero legitimate ability to pay.

Theft generates even more extreme violence:

“No one in prison will tolerate stealing. Anyone caught stealing will likely be beaten to the brink of death and most certainly will be thrown out of the dorm. Someone with a known record of theft will not even be allowed into a dorm.”

The COVID sack lunch story illustrated this dynamic perfectly. The violence wasn’t sadistic—it was economic. It served notice that stealing from fellow prisoners crosses a line that stealing from the state does not. But the brutality proves necessary only because hunger creates the incentive to steal in the first place.

The moral gradations prove complex. Some inmates will tolerate small theft when they know the thief is starving: “It’s hard for someone who has a lot of property to miss a single soup or beef and cheese stick every once in a while. And even if they realize one is missing they might let it go knowing that the thief was just hungry.”

But others won’t tolerate any loss. And no one can predict which response they’ll face until after they’re caught. The uncertainty makes theft terrifying even when necessary.

The hierarchy of prison violations places only one offense worse than theft: snitching. Informing administration about other prisoners’ activities “can easily get you killed.” This proves “extremely rare though, everyone knows the consequences.”

The result is a complete breakdown of legitimate authority. Prisoners can’t report crimes without facing death. They must handle conflicts themselves, through violence, because the state has created a governance vacuum that gangs and individual enforcement must fill.

This is what Georgia’s policies create: a system where violence isn’t a bug—it’s the feature that makes survival economics function.

The Criminal Mindset Factory: How Prison Teaches Crime

The Georgia Department of Corrections claims rehabilitation as its mission. The reality is precisely the opposite. Georgia’s prisons don’t reform criminal thinking—they teach it, reinforce it, and ensure people leave more criminal than when they entered.

Consider what an inmate must learn to survive:

Rule-breaking as necessity: You cannot eat adequately on provided meals. Therefore, you must obtain contraband food—either by stealing it, buying stolen food, or trading for it. Following the rules means starving.

Economic crime as survival skill: You cannot earn money legitimately. Therefore, you must develop underground income—selling stolen food, making alcohol, providing illegal services, or stealing from others. Legal employment isn’t an option.

Violence as enforcement: You cannot rely on authority to protect property or resolve disputes. Therefore, you must either align with gangs who provide violent enforcement or accept victimization. The state won’t help you.

Concealment as standard practice: You cannot report crimes without facing retaliation. Therefore, you must hide violence, treat injuries illegally, and maintain omerta. Cooperation with authority means death.

These aren’t criminal values that rehabilitation should eliminate. These are survival strategies that the GDC’s policies make mandatory. Every day of incarceration reinforces the lesson: crime works, legitimate paths don’t exist, and authority cannot be trusted.

Now consider what happens when someone internalizes these lessons for 5, 10, 15 years, then gets released.

Rabbit: A Case Study in System-Generated Failure

After 15 years in Georgia prisons, a man we’ll call Rabbit was released with nothing. Not nothing metaphorically—nothing literally. No money, no housing, no transportation, no job, no plan beyond survival.

The first months of freedom read like a case study in how Georgia’s zero-wage policy ensures recidivism:

Month 1: Living in the woods. Bought a bucket “so I would not catch the woods on Fire” when cooking. A debt from before prison—$10,400 from an accident—blocks his driver’s license. He can’t get a job without a license. He can’t pay the debt without a job. The loop has no exit.

Month 2: Still homeless. “There’s no work, no places to stay, nothing.” Has assets in Tennessee but can’t access them—probation restrictions prevent crossing state lines. An elderly man buys his dinner “because I was running out of cash.”

The money Rabbit made in prison—$2,500 saved by selling food stolen from the kitchen—was being held by another inmate. That inmate spent it all. Rabbit wrote it off: “I’m not mad at him. He’s just someone else I know that’s not good with money… I can write that $2500 off no big deal. I mean I do need it but what I would go through to get it I would rather write it off.”

Month 4: Finally got a state ID and food stamp approval. Still can’t get a driver’s license—the debt remains. Still homeless, now living in a borrowed car at a gas station. “I stay broke but that’s okay. I’m making progress.”

Month 5: Hospitalized for two days. “I didn’t want to go, but it was an emergency. I have no money to pay the hospital bill.”

Month 6: Bought a bike “because I can’t keep walking everywhere.” Technology illiteracy creates constant vulnerability: “I spent 15 years in prison and the world is so different now. There are so many scams out there… I don’t know much about this online stuff.”

Month 7: Bike accident. Hand broken in three places, stitches above his eye, black eye, injured knee. Needs surgery. “Don’t know if they will do the surgery because I don’t have insurance and no job, and no way to pay.”

Month 10: Still uncertain about surgery. Still living in the borrowed car. Has made “progress”: obtained ID, birth certificate, Social Security card on the way. Still broke. Still no license. Still no job. Still no housing.

The last contact: A video of Rabbit living in the woods with three pet raccoons. His location and condition after that are unknown.

This is what Georgia’s zero-wage policy creates. Rabbit left prison exactly as the GDC designed him to leave: broke, unskilled, traumatized, and expert only in survival strategies that don’t work outside prison walls. He learned to steal food to survive. He learned to distrust authority. He learned that crime is necessary and legitimate paths don’t exist.

Those lessons served him in prison. They guaranteed failure upon release.

If Rabbit returns to prison—and the statistics suggest he likely will—Georgia will count him as a recidivist and claim his failure proves criminals can’t be rehabilitated. The truth is precisely the opposite: Georgia systematically ensured he would fail by refusing to pay him, feed him adequately, or teach him anything except crime.

The question isn’t why Rabbit struggled. The question is how anyone survives this system at all.

The Solution Georgia Refuses: Pay Them

Every problem documented in this investigation traces to a single policy decision: paying prisoners nothing for their labor while providing inadequate food and charging premium prices for necessities. Change that policy, and you eliminate forced criminality, reduce violence, and enable actual rehabilitation.

The evidence for wage-based reform is overwhelming:

Worth Rises and Edgeworth Economics calculated that paying fair wages would generate $26.8 to $34.7 billion in annual societal benefits through increased earnings for workers and families, child support payments of $308-431 million annually, crime victim restitution, tax revenue, and reduced recidivism.

Research in the Journal of Human Resources found that a $1.00 minimum wage increase produces a 1.49 percentage point decrease in three-year recidivism rates. Participants in correctional industries programs show 22% recidivism versus 39% nationally—a 43% reduction. Norway’s prison system pays inmates €4.10 to €7.30 per hour ($5.30 to $9.50) and achieves 20% reconviction rates within two years compared to America’s 76.6% re-arrest rate within five years.

The economic argument proves irrefutable: every dollar spent on fair prison wages returns $2.40 in benefits to workers, families, government, and the broader economy.

But the benefits extend far beyond economics:

Paying wages eliminates theft incentives. Workers with legitimate income don’t risk losing jobs by stealing. Kitchen work becomes actual employment rather than theft access. The food theft documented throughout this investigation—from individual meals to $1,000-daily warehouse operations—becomes unnecessary.

Paying wages eliminates the underground economy’s violence. When people can earn money legitimately, they don’t need to make alcohol, steal commissary items, or create hustles that generate debt and violent enforcement. The COVID sack lunch beating never happens because the thief isn’t desperate. The drug debt beatings don’t happen because addicts can pay from wages rather than hoping family sends money.

Paying wages provides reentry funds. Rabbit’s post-release disaster resulted directly from having zero savings. If he’d earned $7.25/hour for 40 hours weekly during his 15 years—the federal minimum wage—he’d have saved $226,200 before paying for commissary, phone calls, or sending money to family. Even saving just 10% would have provided $22,620 for reentry—enough for first and last month’s rent, a security deposit, work clothes, and months of survival while finding employment.

Most critically, paying wages replaces criminal survival strategies with work ethic. The lesson inmates learn shifts from “crime is necessary for survival” to “legitimate work provides for needs.” The question Georgia should ask isn’t “Would you rather have a prisoner get released into your community who still have a criminal mindset or one who knows he can work legitimately to survive?” The question is “Why are we deliberately teaching the criminal mindset and then acting surprised when they use it?”

Seven states have removed the 13th Amendment’s slavery exception from their constitutions since 2018—Colorado, Utah, Nebraska, Alabama, Oregon, Tennessee, and Vermont. Senator Cory Booker’s federal “Abolition Amendment” proposes removing it from the U.S. Constitution. Multiple state bills in New York, California, Nevada, and Connecticut propose wage requirements for prison labor.

Georgia could implement this tomorrow. Commissioner Tyrone Oliver has administrative authority to establish wage schedules without legislative approval. The state budget already accounts for operational costs that unpaid labor currently covers—paying inmates would simply shift existing expenditures from indirect (security, healthcare, violence management) to direct (wages that reduce all three).

The Deliberate Design of Failure

Georgia’s prison system functions exactly as designed. Not to reduce crime, rehabilitate offenders, or protect public safety. But to extract maximum economic value from predominantly Black and poor populations while maintaining social control through systematically generated desperation.

The state pays nothing for labor worth millions. It feeds people inadequately then charges them premium prices for supplemental food through a commissary system that extracted $18.76 million in profit in 2024. It creates conditions so unbearable that survival itself requires breaking rules, then punishes rule-breaking while ignoring the policies that make it mandatory. It forces people to steal, make alcohol, join gangs, hide violence, and learn that crime works while legitimate paths don’t exist.

Then it releases them with nothing, no skills except crime, and a mindset conditioned by years of learning that authority cannot be trusted and rules must be broken to survive.

When they return—and 76.6% do within five years—Georgia calls them recidivists and uses their failure as evidence that criminals cannot change. The truth is that Georgia ensures they cannot change by designing a system that teaches crime, rewards it, and makes it necessary for survival.

The DOJ found 142 homicides from 2018-2023, with a 95.8% increase between periods. That violence isn’t random. It’s not the inevitable result of housing criminals. It’s the predictable, mathematical consequence of policies that create desperation, eliminate legitimate survival options, and then abandon oversight so thoroughly that gangs provide the only governance that exists.

Every beating over stolen food traces to zero wages and inadequate meals. Every drug debt collection traces to the stress of confinement without legitimate coping mechanisms. Every gang taxation scheme traces to the state’s refusal to provide what people need to survive. Every hidden stab wound treated by untrained medics traces to medical neglect and fear of collective punishment. Every dollar Rabbit didn’t have traces to 15 years of unpaid labor.

Bryan Stevenson of the Equal Justice Initiative captured the moral clarity required: “Slavery did not end in 1865. It just evolved.”

The constitutional loophole enabling this evolution—the 13th Amendment’s exception for “punishment for crime”—provided legal permission for convict leasing that killed tens of thousands, chain gangs that worked men in literal chains, and contemporary unpaid labor that generates billions in value while paying nothing to workers.

Georgia stands at a choice point. Continue operating the world’s most aggressive incarceration system built on forced unpaid labor, manufactured starvation, systematic exploitation, and violence that makes prisons among the nation’s most dangerous. Or recognize that paying people for their work, feeding them adequately, and teaching legitimate survival skills isn’t charity—it’s the bare minimum required to claim any rehabilitative purpose.

The evidence for change is overwhelming. The moral imperative is undeniable. The economic benefits are proven. The only barrier is political will to challenge a system that profits from poverty and pain.

As one prisoner summarized the entire crisis: “I work hard every day at my detail and don’t get paid anything. But they expect me and my family to pay 30% more next year for the things I need to survive. I only have two options: buy from these crooks or wither away and die.”

He was wrong. Georgia has given him a third option: break the rules, steal what you need, participate in underground economies, learn that crime works, and carry that lesson back to the streets when released.

The question isn’t whether Georgia’s prisons create criminals. The question is why we pretend to be surprised when they do.

Call to Action: Demand Fair Wages and End Forced Criminality

Georgia’s prison violence crisis will continue until the state addresses its root cause: policies that force criminality as a survival strategy. Here’s how you can demand change:

1. Use ImpactJustice.AI to Contact Decision-Makers

ImpactJustice.AI is a free tool that generates professional, personalized letters citing the evidence from this investigation.

Send messages directly to:

- Commissioner Tyrone Oliver and GDC Leadership – demanding fair wages for prison labor

- Governor Brian Kemp – requesting executive action on prison wages

- Your State Legislators – supporting wage requirements and the Abolition Amendment

- Media Outlets – amplifying this investigation

Choose from different communication styles and send your letter in minutes. Each message cites verified data from GPS investigations.

2. Contact Georgia Department of Corrections Leadership

Commissioner Tyrone Oliver has administrative authority to establish wage schedules for prison labor without legislative approval.

Demand he:

- Implement fair wages for all prison work (minimum $7.25/hour federal minimum wage)

- End the zero-wage policy that forces underground economies

- Address the nutrition crisis driving theft and violence

- Provide adequate mental health and substance abuse programming

Contact Information:

- Email: tyrone.oliver@gdc.ga.gov

- Phone: (404) 656-4593

- Mail: Georgia Department of Corrections, 300 Patrol Road, Forsyth, GA 31029

Sample message:

“Commissioner Oliver: Your department documented 100 homicides in 2024 alone. This violence is the direct result of zero-wage policies that force prisoners into underground economies. Implement fair wages immediately to eliminate theft incentives, provide reentry funds, and replace criminal survival strategies with legitimate work ethic. The evidence is overwhelming: paying wages reduces violence, lowers recidivism, and saves taxpayer money.”

3. Contact the Governor

Governor Brian Kemp can direct the Commissioner to implement wage policies and support legislative reform.

Governor Brian Kemp:

- Website: gov.georgia.gov/contact-us

- Phone: (404) 656-1776

- Mail: 206 Washington St, Suite 203, State Capitol, Atlanta GA 30334

What to demand:

- Direct Commissioner Oliver to implement fair wages for prison labor

- Support the Georgia Abolition Amendment removing the 13th Amendment slavery exception

- Order independent investigation of the 34-homicide discrepancy (100 GPS-documented vs 66 official)

- Mandate transparency in prison mortality reporting

4. Contact Your State Legislators

Georgia’s 2026 legislative session begins in January. Now is the time to demand lawmakers support prison wage reform.

Find your legislators: openstates.org/find_your_legislator or legis.ga.gov/members/find-my-legislator

Ask them to:

- Co-sponsor and support Georgia’s Abolition Amendment removing the slavery exception from the state constitution

- Require fair wages for all prison labor (federal minimum wage at minimum)

- Hold oversight hearings on the violence crisis and the 34-homicide reporting discrepancy

- Investigate GDC’s zero-wage policy and its role in generating violence

- Support Senator Cory Booker’s federal Fair Wages for Incarcerated Workers Act

Key talking points:

- Worth Rises study: Fair wages generate $26.8-34.7 billion in annual societal benefits

- Research shows $1.00 wage increase = 1.49 percentage point recidivism reduction

- Norway pays prisoners €4.10-7.30/hour, achieves 20% reconviction vs. America’s 76.6%

- Every dollar spent on fair wages returns $2.40 in benefits to society

5. File Federal Complaints

U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division (CRIPA):

The DOJ is already investigating Georgia prisons. Your testimony strengthens their case.

Report:

- Zero-wage policies creating forced criminality

- Violence resulting from underground economies

- Gang control of basic necessities

- Inadequate nutrition forcing theft

- Medical neglect requiring underground healthcare

- Staff awareness and complicity

File complaints: civilrights.justice.gov/report

Document everything: Names, dates, facilities, specific incidents connecting economic desperation to violence.

6. Support Federal Legislation

Senator Cory Booker’s “Abolition Amendment” would remove the 13th Amendment’s slavery exception from the U.S. Constitution.

Senator Cory Booker’s “Fair Wages for Incarcerated Workers Act” (S.516) would extend Fair Labor Standards Act protections to require federal minimum wage for all prison work.

Contact your U.S. Senators and Representatives:

- Find them: www.congress.gov/members/find-your-member

- Demand they co-sponsor both bills

- Share this investigation as evidence for why these reforms are urgent

7. Share This Investigation

The public’s silence enables the GDC’s violence. Breaking that silence is the first step toward justice.

Share on social media:

- Tag with #ForcedCriminality #GeorgiaPrisons #EndPrisonSlavery #PrisonReform

- Tag @GeorgiaDOC and @GovKemp to demand accountability

- Share with criminal justice reform organizations, advocacy groups, and journalists

Talk about it:

- At church, work, schools, and community organizations

- With local journalists covering criminal justice

- In letters to the editor of your local newspaper

Support families:

- Write, call, and send funds through approved channels

- Families are the last line of defense for those inside

- Every connection helps someone survive this system

8. Submit Your Story to GPS

Have you or a loved one experienced:

- Kitchen theft for survival?

- Violence over food, debt, or gang taxation?

- Release with zero savings after years of unpaid labor?

- Gang control of basic necessities?

- Underground medical treatment?

Your testimony builds the case for reform.

Submit stories safely: gps.press/story-submission or email accountability@gps.press

You may remain anonymous. Journalistic privilege protects your identity.

9. About GPS

Georgia Prisoners’ Speak (GPS) is an independent, prisoner-centered journalism and advocacy project dedicated to exposing the violence, corruption, and systemic failures the state works hard to hide. We operate without government funding, without institutional backing, and without permission — because the truth coming out of Georgia’s prisons must be told.

Our investigations rely on:

- Secure communication with incarcerated sources who risk retaliation to tell the truth

- Legal research, open-records work, and FOIA requests the state often obstructs

- Data verification and analysis to counter GDC narrative manipulation

- On-the-ground reporting from families, whistleblowers, and current/former staff

- Protection for sources and journalists, especially those still inside

- Digital tools like ImpactJustice.AI to translate findings into real-world action

GPS exists for one purpose: to give the people living and dying inside Georgia’s prisons a voice powerful enough to demand change.

If you value independent reporting that exposes what officials deny, minimizes, or hide altogether, support our work by:

- Sharing this investigation

- Submitting credible information or stories

- Using ImpactJustice.AI to amplify these findings

- Encouraging others to follow and support GPS

Every story we publish strengthens the public record, protects the people still inside, and pushes Georgia one step closer to accountability, transparency, and justice.

The Time to Act Is Now

Georgia documented 100 prison homicides in 2024—nearly triple the previous year’s record. The 2026 legislative session begins in January. The current commissary contract expires June 30, 2026. Commissioner Oliver has authority to implement wages immediately.

Every day Georgia delays costs lives.

The evidence is overwhelming: zero wages force underground economies that generate violence. Fair wages eliminate theft incentives, provide reentry funds, reduce recidivism, and save taxpayer money.

The solutions exist. Other states and countries have proven they work. The only barrier is political will.

Make your voice heard. Georgia’s prisoners cannot speak for themselves—but you can speak for them.

This is the second article in a two-part series examining poverty as the driving force behind both mass incarceration and prison violence in Georgia. Read Part 1: “The Poverty-to-Prison Pipeline: How Georgia Criminalizes Being Poor.”

Related Investigations:

Further Reading & Related Investigations

To understand the full scope of Georgia’s prison crisis and the solutions that could end forced criminality and violence, explore these related investigations:

This Investigation Series

The Poverty-to-Prison Pipeline: How Georgia Criminalizes Being Poor

Part 1 of this series examining how poverty outside prison feeds mass incarceration through cash bail, fines and fees, and a system designed to extract wealth from poor and Black communities.

America’s Hidden Crime: How the Government Poisoned a Generation, Then Imprisoned Them for It

Part 1 of our Investigation reveals U.S. government knowingly allowed lead poisoning for 70 years, causing violent crime epidemic—then blamed “superpredators” and imprisoned millions instead of addressing the neurotoxin they permitted. Academic research proves 8 million tons of lead from gasoline damaged children’s brains, and crime declined when we stopped poisoning kids—not from mass incarceration.

Exposes the two-tier markup scheme where near-expired products are sold at 400-900% markups, extracting $18.7 million annually from families—the economic exploitation that forces prisoners into underground economies.

Starved and Silenced: The Hidden Crisis Inside Georgia Prisons

Documents the nutrition crisis driving forced criminality: 1,200-1,400 calories daily, deliberate portion reduction, and how malnutrition directly fuels violence and desperation.

Nutrition Neglect: How Georgia’s Prison Food Is Fueling Violence

Examines the science connecting inadequate nutrition to aggression, showing how basic vitamin supplements reduce violence by 37%.

Violence and Crisis Documentation

THE FIGHT TO SURVIVE: INSIDE GEORGIA’S DEADLY PRISON CRISIS

GPS’s comprehensive investigation into the 330 deaths in 2024 (100 by homicide), gang control, and the DOJ’s constitutional findings.

The Hidden Violence in Georgia’s Prisons: Beyond the Death Toll

Documents that for every homicide, 12-18 others are stabbed or beaten—nearly 1,200 violent incidents annually that the state never counts.

When Warnings Go Ignored: How Georgia’s Prison Deaths Became Predictable—and Preventable

Shows how Georgia’s prison deaths aren’t accidents but policy choices, comparing Georgia’s 333 deaths to California’s single death despite similar spending.

Lethal Negligence: The Hidden Death Toll in Georgia’s Prisons

Exposes how protective custody failures, gang-controlled facilities, and document falsification allow murders to continue with impunity.

Violence And Corruption Unleashed: The Truth About Washington SP

Investigates the murder of Dontavis Carter and the chaos at Washington State Prison where gangs wield unchecked power.

From Kangaroo Courts to Chaos: Georgia’s Prison Crisis

Documents how Georgia’s disciplinary system punishes victims while protecting gang attackers, creating more violence instead of preventing it.

Solutions: Decarceration and Reform

Decarceration as a Solution to Georgia’s Prison Crisis

Shows how releasing elderly and long-term low-risk inmates would reduce overcrowding, save money, and improve safety based on successful models from other jurisdictions.

Decarceration: The Key to Solving Georgia’s Prison Staffing Crisis and Healthcare Burden

Makes the economic case: reducing prison population addresses understaffing, lowers healthcare costs, and reduces violence.

Downsize to Rightsize: Georgia’s Prison Crisis Needs Urgent Action

Demonstrates that decarceration isn’t just compassionate—it’s necessary for safety, management, and basic human dignity.

A Tale of Two Prisons: What Georgia Can Learn from Norway

Compares Georgia’s violence-breeding system to Norway’s humane approach that pays wages, treats people with dignity, and achieves 20% recidivism.

Prisneyland: What Prison Should Be

Shows California’s Valley State Prison achieved zero homicides through education and rehabilitation—proving reform works.

Outlines immediate steps that would reduce violence: separate gangs, restore tablets, provide yard time, end triple bunking, fix the food, and prosecute murders.

Parole Reform

Fixing Georgia’s Parole System: The Ultimate Plan for Justice

Advocates for tying parole to rehabilitation and accountability, with transparency measures to end arbitrary denials.

A Second Chance for Georgia: Fixing Parole With the Reform It Desperately Needs

Proposes the Second Chance Parole Reform Act to address systematic parole denials keeping people imprisoned for decades.

Parole: A Promise Broken — and How Georgia Can Make It Right

Documents how Georgia’s parole system has become a broken promise, with families waiting years while the state refuses to release eligible prisoners.

Systemic Failures and Corruption

The Crisis of Deception and Mismanagement in Georgia’s Prison System

Based on AJC and DOJ investigations exposing deception, systemic failures, and inhumane conditions.

Broken: The Urgent Need for Reform in Georgia Prisons

Documents severe understaffing, rising violence, and deteriorating conditions demanding immediate reform.

Exposé: How Georgia’s Justice System Functions as a Criminal Enterprise

Reveals corruption from smuggled contraband to hidden evidence and retaliated whistleblowers.

Unqualified and Unprepared: Leadership Failure in Georgia’s Prisons

Shows how decades of insular promotions and inadequate training created a leadership vacuum with devastating consequences.

Living Conditions

Triple Bunking Crisis: The Harsh Reality Inside Georgia Prisons

Documents men stacked three to a cell designed for one—humanitarian crisis driving violence and desperation.

Heat, Humidity, and the Constitution

Examines how extreme temperatures in Georgia prisons violate constitutional rights, comparing to successful Texas lawsuit.

Caged and Forgotten: The Hidden Horrors of Valdosta State Prison

Investigates conditions at Valdosta that rival El Salvador’s notorious CECOT prison.

Economic Exploitation Beyond Forced Labor

Who’s the Real Criminal? How Georgia Steals money

Documents how commissary funds vanish into a black hole with no audits while wardens use inmate funds for staff perks.

The Price of Love: How Georgia’s Prisons Bleed Families Dry

Shows families spend 6% of household income monthly on prison costs—financial strain that perpetuates cycles of poverty.

Punishment for Profit: How Georgia’s Justice System Makes Millions

Exposes how being poor, mentally ill, or addicted becomes criminalized for profit.

Slavery by Another Name: Forced Labor in Georgia Prisons

Documents how unpaid prison labor continues slavery’s legacy under the 13th Amendment’s exception clause.

The Broader Context

What Happens in Prison Doesn’t Stay There

Shows how prison conditions impact communities when 95% of prisoners eventually return home.

Unconstitutional: Georgia’s Extrajudicial Punishment

Argues that violence and neglect inside exceed sentences handed down by judges—creating unconstitutional punishment.

Georgia’s Corrections Spending vs Public Safety: A Costly Imbalance

Documents billions spent on incarceration producing only average safety outcomes—showing the system doesn’t work.

Government Reports

Investigation of Georgia Prisons – U.S. Department of Justice

The October 2024 DOJ report documenting 142 homicides, 14,000+ gang members, 52.5% officer vacancies, and constitutional violations.

Georgia Prisons: The AJC’s Investigation

Multi-part series on corruption, falsified data, and record violence.

National Research

Cost-Benefit Analysis: Ending Slavery in Prisons – Worth Rises

Shows fair wages generate $26.8-34.7 billion in annual societal benefits.

Minimum Wage, EITC, and Criminal Recidivism – Journal of Human Resources

Research showing $1.00 wage increase = 1.49 percentage point recidivism reduction.

Prison Gangs, Norms, and Organizations – Journal of Economic Behavior

David Skarbek’s research on how gangs provide governance in prison underground economies.

Take Action

How a Simple Tool Is Helping Georgians Fight Back: Impact Justice AI

Learn how this advocacy tool has generated over 15,000 messages to lawmakers and media demanding reform.

Generate professional letters to Georgia officials, legislators, and media citing evidence from GPS investigations.

Georgia Prisoners’ Speak is an independent publication dedicated to exposing conditions in Georgia’s prison system through rigorous investigative journalism. Support our work at gps.press.

2 thoughts on “Forced Criminality: Inside Georgia’s Prison Violence Factory”